Cuauhtémoc's bones, Ixcateopan

On 2 February 1949 a villager in Ixcateopan named Salvador Rodríguez Juárez found some papers hidden behind a shrine to the Virgin of Asunción in his home. Among the papers were an eighteenth-century book with some marginalia and an eight-page booklet in a leather cover. Both were signed by the colonial-era Franciscan friar Toribio de Benavente, known as Motolinía. They appeared to indicate that the last Mexica emperor, Cuauhtémoc, was a native of Ixcateopan and had been buried in the village church. Rodríguez Juárez consulted the village priest about what to do with the papers, and the priest disclosed the astounding discovery at a Sunday mass. An official from a nearby town who attended the mass told a landowner from his village who worked as a stringer for the major Mexican daily El Universal. The news spread quickly.

The revelations could not been more timely for General Baltasar Leyva Mancilla, the governor of the state, who was deep in a political crisis that threatened his overthrow. By 1949 his administration had opposed President Aleman's election and overseen two rebellions and a lengthy string of political murders: his violent mismanagement of the December 1948 municipal elections had further fuelled already bitter peasant opposition. Against this dark backdrop, the opportunity to produce the long-lost body of Cuauhtémoc was a lifeline. So Leyva Mancilla moved with some urgency, forming a state commission, and then seeking help from the Instituto Nacional de Historia e Antropología (INAH) in Mexico City. The INAH in turn commissioned Eulalia Guzmán, who had spent several years in Europe locating and transcribing Mexican codices and had written a manuscript on Hernán Cortés’s Relaciones.

Once in Ixcateopan, Guzmán would have realized at once that something was amiss with the documents. Motolinía could not have penned marginalia in a book published more than two hundred years after his death. Guzmán nonetheless went ahead with her investigations, returning to the village several times between February and September, and accumulating additional evidence in support of the authenticity of the burial. Still unsure about the truth of the matter, she believed that archaeological explorations in the church could provide definitive confirmation or refutation, and she asked the INAH to appoint an archaeologist. When the commissioned archaeologist was waylaid, the governor decided the excavation should begin anyway. After a few days of digging under the church altar and past three sets of floors, on 26 September villagers uncovered a pile of stones reminiscent of a pre-Columbian ritual mound. Below, there was a stone slab. Finding a gap in the stone, the diggers hit softer mud. A pick went through it, releasing a foul cuprous odour. Lifting some stone, the crew found a dagger and a copper plaque. The plaque was engraved with the numbers 1,525 and 1,529 separated by a cross and, below, “Rey, é, S, Coatemo.” Lifting the plaque, the assembled villagers saw a cranium with some beads in it. They unearthed more bones. Cuauhtémoc’s remains had been found!

Politicians and bureaucrats reacted immediately and launched an intensive nationalist campaign. Congressmen and senators organised homages, fed carefully impassioned soundbites to the press and passed a resolution calling for a colossal monument.

Since then, the story has largely been debunked, with the documents and placing of the bones, which came from several bodies, attributed to Salvador Rodríguez Juárez’s forebear, Florentino Juárez. However, Ixcateopan’s reputation as Cuauhtémoc’s hometown remains and the village now celebrates his birthday with singing and dancing.

This note, though not paper money, is a receipt for a contribution to the fund to build a monument to Cuauhtémoc in Ixcateopan.

M Unlisted $5 Certificado de Aportación

M Unlisted $5 Certificado de Aportación

| Series | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| $5 | D | includes number 9527 |

The vignette of Patria is based on the vignette on the Gobierno Provisional de México notes and her shield carries the date, 28 February 1525, the day of Cuauhtémoc's execution by Hernán Cortés in Honduras. The signature is of the governor, Baltazar Reyes Leyva Mancilla, as Presidente del Patronato.

|

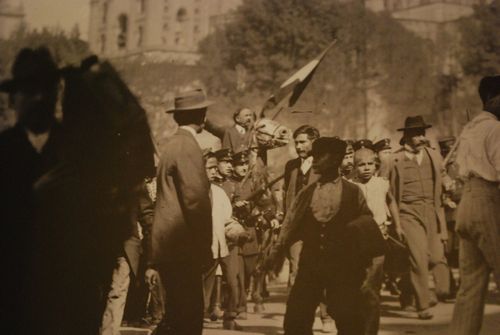

Baltazar Reyes Leyva Mancilla was born in Chilpancingo, Guerrero, on 6 January 1896. In 1913, as a cadet at the Heroic Military College, he participated in a group of these escorting Francisco I. Madero in the so-called March of Loyalty, a route that took place from the Castle of Chapultepec to the National Palace in Mexico City on February 9, right at the beginning of the so-called Decena trágica. On 1 April 1945, he took office as constitutional governor of Guerrero. During his term, He completed and inaugurated important works in the port of Acapulco that marked the beginning of its modernization and development in infrastructure and tourism. In 1952, a year after the end of his governorship, he held the position of Oficial Mayor of the la Secretaria de la Defensa Nacional. He died on 21 September 1991. |

La Marcha de la Lealtad