Counterfeits of Iturbide’s Paper Money

On 19 May 1822 Agustín de Iturbide, the victor in the War for Independence, was proclaimed “Agustín the First, by the Grace of God Emperor of Mexico” and later, on 21 July of the same year, he was crowned in pomp and splendour with the growing enthusiasm of his followers: the conservative circles, the army and the general populace.

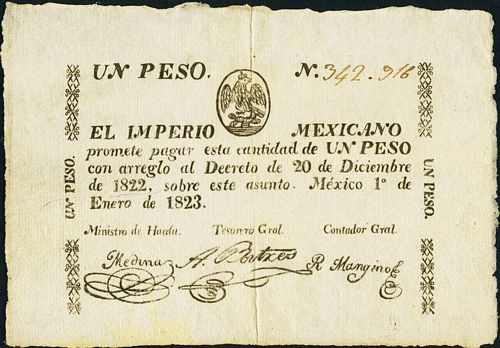

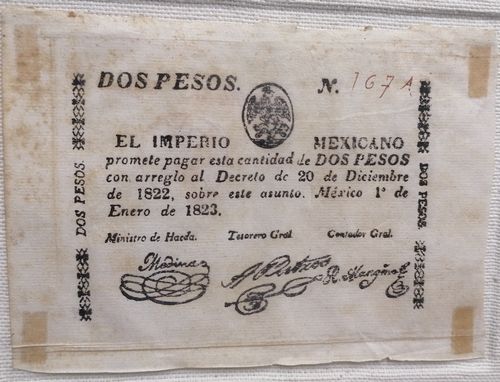

Because of the catastrophic economic situation that the new government faced, the Minister of Finance (Ministro de Hacienda), Antonio de Medina, requested authorization to issue paper money and on 20 December 1822 authorized the issue of cedulas, in $1, $2 and $10 denominations, for the total amount of four million pesos. The decree specified that these new notes should be valid from 1 January to 31 December 1823, and a later clarification stipulated that they should be gradually withdrawn from circulation, by being received by the tax collection offices and cancelled by means of a diagonal cut in de Medina’s signature.

This paper money supposedly circulated in all the vast Empire from the immense territories in the North (including California and Texas) to its provinces in Central America. A total of $1,535,000 was put into circulation, comprising 797,000 $1 notes, 184,000 $2 notes and 37,000 $10 notes. However, from the very first the notes met with repugnance and distrust from all strata of the population. Then, after Iturbide was forced to abdicate on 19 March 1823, the issue was suspended. Congress ordered the complete destruction of printed notes and the remaining blank paper, as well as of the plates that had been used for their impression, and issued orders calling in all the paper money that was in circulation or in the local government treasury offices so that it be accumulated in one place and destroyed. As of 3 November 1823 $245,131 remained in circulation but there were further exchanges thereafter.

Contemporary counterfeits

By 23 May 1823, just four months after Iturbide’s paper currency was introduced, a number of counterfeit $1 and $2 notes had appeared in Mexico City, either used in daily transactions or handed in to the Treasury for redemption. The Judge (Juez de Letras y Hacienda Pública) José Rafael Suárez Pereda was ordered to start an investigation, some people were held in detention, and from that date until January a selection of enquiries were held, witnesses were questioned and experts gave evidence. In the beginning, when the judge asked for two expert witnesses, Mariano Larriguibel was proposed as the only person with full knowledge but he was too busy stamping and numbering the bulas, introduced as a replacement for Iturbide’s first issue: however, he gave evidence a couple of days later, along with the engraver (grabador) José Manuel de Araoz, Joaquín Piña and Francisco Dimas Rangel.

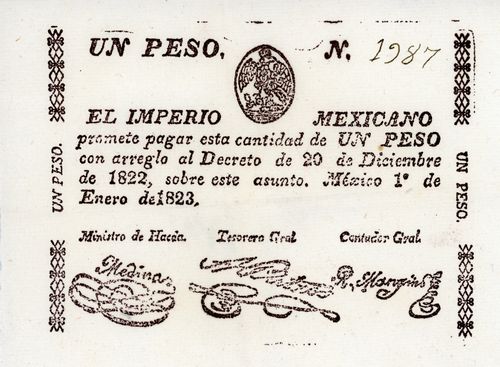

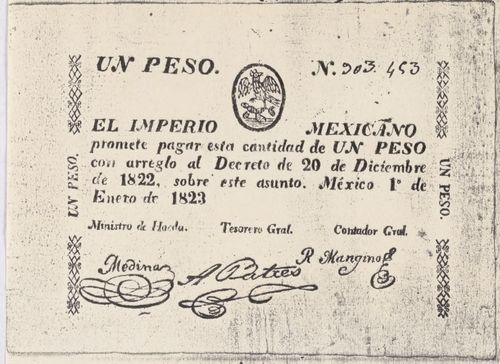

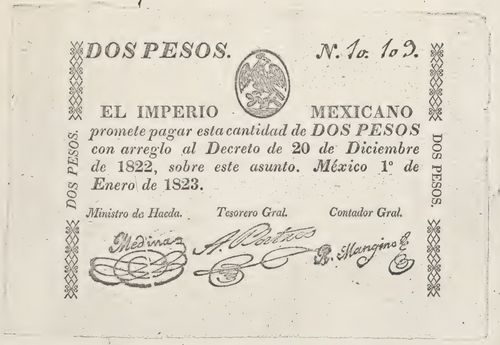

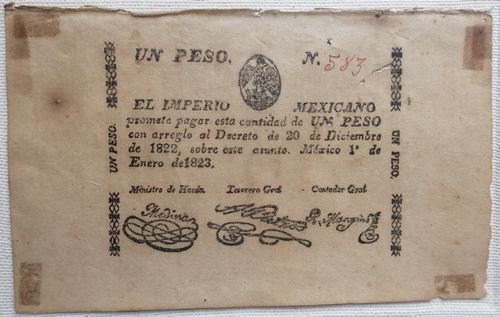

Over time the experts outlined a few ways in which the counterfeit notes differed from the genuine article. On 4 June they reported that the most noticeable difference, among others in the character, size and form of letter and design (guarnición) was that on two of the four notes printed on a half page the date appeared as ‘1o de Enero de1823’ without a space between the ‘de’ and ‘1823’.

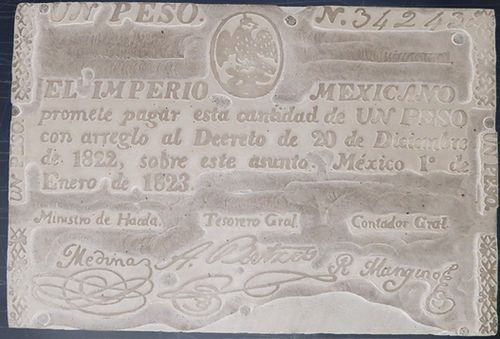

Strangely, this (glaring) error is noted on the modern counterfeit $1 notes illustrated below. This suggests that the modern counterfeiter copied from a contemporary counterfeit.

Suárez and Araoz reported that they had noted defects in the various signatures, something that also preocuppied the correspondents in the 1960s, as detailed below. The differences that Suárez and Araoz notes (though I cannot be certain that I have interpreted them fully and correctly) were as follows:

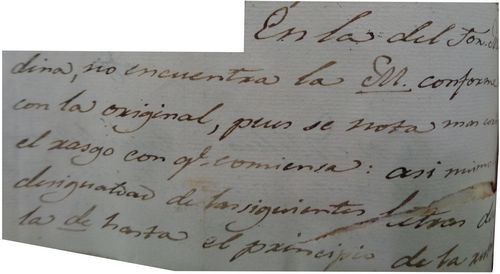

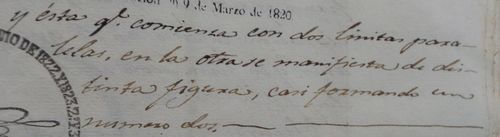

In Medina’s the ‘M’ is different, as the loop with which it begins is shorter: the letters from the ‘d’ are different, and finally the flourish, instead of beginning with two parallel lines, almost forms a number two (En la del Sr. Medina, no encuentra la M conforme con la original, pues se nota mas corto el rasgo con que comiensa: así mismo la designation de las siguientes letras desde la de hasta el principio de la rubrica y ésta que comienza con dos limitas paralelas, en la otra se manifiesta de distintas figuras, casi formando un numero dos).

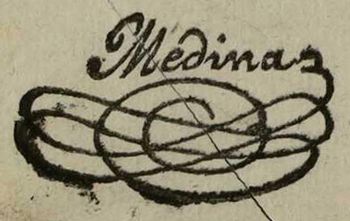

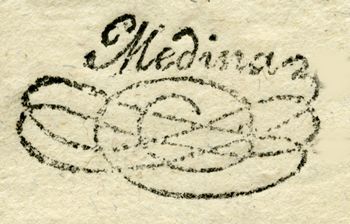

Though I cannot claim that this is the counterfeit referred to, note number 489263 appears to show these features.

Medina's signature on $1 43489 and $1 489263

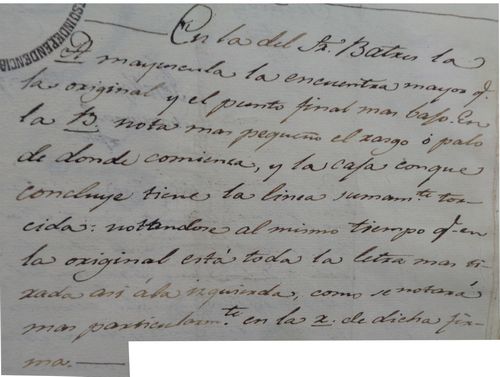

In Batres’ signature the capital‘A’ is higher than the original and the final point lower. In the ‘B’ the feature with which it begins is smaller, and the ‘box’ with which it finishes has the line extremely crooked. In the original all the letters are slanted more to the left, as will be noticed more particularly with the ‘r’. (En la del Sr. Batres la A mayuscula la encuentra mayor q. la original y el punto final mas bajo. En la B nota mas pequeño el rasgo ó palo de donde comiensa, y la caja conque concluye tiene, la línea sumamente torcida: notándose al mismo tiempo que en la original está toda la letra mas girada á la izquierda, como se notará mas particularmente en la r de dicha firma.)

In Batres’ signature the capital‘A’ is higher than the original and the final point lower. In the ‘B’ the feature with which it begins is smaller, and the ‘box’ with which it finishes has the line extremely crooked. In the original all the letters are slanted more to the left, as will be noticed more particularly with the ‘r’. (En la del Sr. Batres la A mayuscula la encuentra mayor q. la original y el punto final mas bajo. En la B nota mas pequeño el rasgo ó palo de donde comiensa, y la caja conque concluye tiene, la línea sumamente torcida: notándose al mismo tiempo que en la original está toda la letra mas girada á la izquierda, como se notará mas particularmente en la r de dicha firma.)

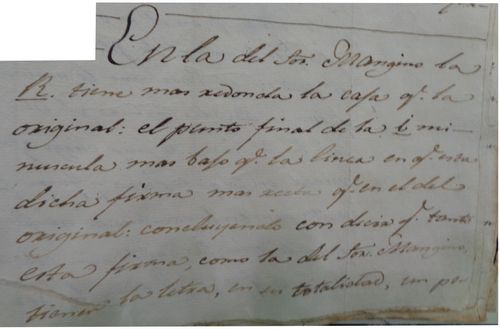

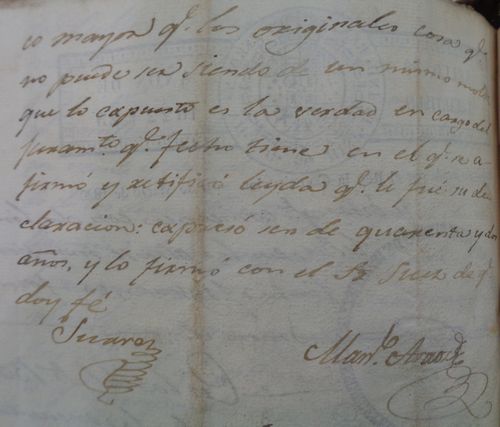

In Sr. Mangino’s signature the ‘R’ has the ‘box’ rounder than the original: the end point of the lowercase ‘i’ is lower than the line in which the said signature is straighter than in the original; concluding with saying that both this signature, and that of Sr. Mangino (?), have the letters, in their entirety, a little larger than the originals (En la del Sr. Mangino la R tiene mas redonda la caja que la original: el punto final de la i minúscula mas bajo que la línea en que esta dicha firma mas recta que en el del original; concluyendo con decir que tanto esta firma, como la del Sr. Mangino, tienen las letras, en su totalidad, un poco mayor que los originales como que no puede ser, )

The ‘box’ is obviously the flourish with which these signatures finish.

To date I have not been able to recognise, in a review of the images that I have collected, definite examples of either of these counterfeit signatures, so once again you might feel short-changed.

However, some member might be able to produce greater details and in the meantime, we have confirmation that the Iturbide notes were counterfeited at the time, and in fact it was the realisation that counterfeits existed, rather than the fall of Iturbide, that prompted the change to the Tesorerías de la Federación printing of notes on the back of Papal bulls.

Modern counterfeits

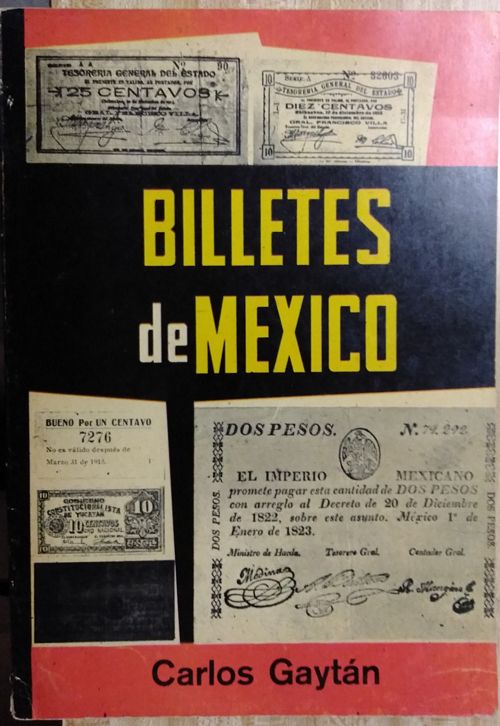

Little was written about this issue although Carlos Gaytan had an image of a (possibly counterfeit) $2 note on his first catalogue in 1965 and recorded that they were very rare. Then in April 1965 the Boletín Numismático of the Sociedad Numismática de México, no. 47, included an article by José Tamborrel, jr., “Shocking Forgery” (available at the USMexNA online library), warning of modern forgeries (though Tamborrel did give not all the information he had as a result of his research).

Soon after, a sizeable quantity of notes appeared on the market. Richard A. Long reported that in late 1968 - early 1969 he was offered singles and quantities, including sheets, and naturally was suspicious (whether genuine or not, a hoard would depress the market, so Long was not interested in buying the notes at any price) and on 28 July 1969 Carlos Gaytan wrote “As to the Iturbide one and two peso notes, ... Mexico is now flooded with them. When I say flooded I mean hundreds. Three or four months ago, a friend of mine was offered forty sets of one-two Iturbide, plus 40 two peso notes for thirty thousand Mexican pesos. He was assured he could easily make a hundred thousand pesos profit. But my friend was wise and declined the offer. A month ago I was offered a set of one-two Iturbides for three hundred pesos,” a special price for me”. I declined and was asked if I thought that the notes were forgeries, and WHY. I refused to answer. Undoubtedly, the forgers were trying to find out about the flaws detected by collectors so as to correct future issues.” On 16 October 1969 Eduardo Rosovsky wrote “In the last two years, I have seen or heard or even have had personally, about a total of 45- 50 sets (ONE & TWO pesos) and I have some by now. But there is another dealer who has also a small quantity. And that is all: nobody, besides both of us, has or can have more then ONE set... But there must be some (maybe 25, perhaps 40 Or even a little more— ONE peso single. About the TEN pesos Iturbide notes, I must call your attention that I am the ONLY ONE that has them, since I had discovered them in some familiar archives; at first, it was one single piece; but I “mobilised” the whole family, and then obtained another three pieces; since then -a year ago-, I have tried unsuccessfully to get more, but without any success, … You see; the TEN pesos Iturbide note, has been known only by the Decree, but NOBODY had ever seen a single one.“

After being offered a sheet of four notes the American numismatist, Ed Shlieker, became interested, particularly in the idea that most of these notes were counterfeits, and tried to arrange a committee under the auspices of the International Bank Note Society to decide the matter. Some of the subsequent correspondence, available as part of the Eric P. Newman correspondence at the Newman Numismatic Portal at Washington University in St. Louis reveals a world not only of co-operation in the leisurely era of letter-writing and black and white photocopies but also of bruised egos, rifts and backbiting. It also gives an insight into a time when less attention seems to have been paid to historical sources than to the pieces in handIn the 1960s numismatists concentrated on the actual notes rather than on the documentary evidence, though Rosovsky was aware of some documents (no doubt, those mentioned below) from which he derived the name of the printer and the description of the paper used.

However, this issue was fully documented at the time and the Secretariá de Hacienda kept copies of the Imperial decrees, its own circulars, and correspondence with the Intendentes of different provinces and various private individuals on the distribution, acceptance (or not), collection and incineration of this issue. A few years later an official called Bermudez reviewed all the documentation, reordered it under various headings and attached his summary (extracto) of each section. These documents and the summaries can now be found in the Archivo General de la Nación (AGN) in Mexico City as Archivo Histórico de Hacienda, volume 1873, expedientes 1 to 13 and volume 1874, expedientes 2 to 19.

In his time, Román Beltrán was a historian who collected original manuscripts and also typed up a host of royal ordinances, mining laws, contracts to smelt gold and licenses for silversmiths, accusations and judicial litigation and matters concerning gold, silver and jewelry that the prosecutors of New Spain took to the Spanish king, and studies on the history of currency in Mexico. Luckily, Beltrán laboriously typed up most of the documents in the Archivo General de la Nación concerning Iturbide’s issues, saving us the trouble of trying to decipher these (though, to be fair, the original handwriting is surprising clear) and reproducing most of the original orthography and intriguing abbreviations.

Finally, the Centro de Estudios de Historia de México was founded in 1965 (at a time when too much of Mexico’s archival records was ignored, being destroyed or being sold to private collectors or libraries and archives in the States) as an institution devoted to the research, preservation and dissemination of Mexico’s historical prints and documents from the viceregal era to the present day. It is now owned by the Fundación Carlos Slim, so is known as Carso CEHM. The centre’s archives contain around 700 documentary resources (about two million pages), and its library has over 80,000 books. Now included in its archives is its Fondo VIII-4 Manuscritos de Román Beltrán.

Fifteen years ago one would have had to visit the Centro itself, located in the pleasing tiny plaza Federico Gamboa, in the old barrio of Chimalistac, around the corner from site of the restaurant where Alvaro Obregon was assassinated. Around ten years ago the Centro started to put some documents online but the website was hard to navigate, the search facility discouraging and the content limited. Nowadays it is easy to dip into the online archive and read all Beltrán’s transcripts.

Beltrán seems to have overlooked another source in the AGN. This is filed as Civil-Volúmines, volume 1402, expediente 20 and records an investigation, in May 1823, on the subject of counterfeit Iturbide notes.. Shlieker meticulously examined his notes and recorded his findings as to paper, ink, watermarks and method of production. He was particular interested in their fresh appearance and the quality of ink and paper, believing that 146 year old notes would show signs of aging. “It is impossible for me to believe that all these notes were maintained in a peak of preservation, unless they are not 146 at years old”. “The ink inscriptions are in a remarkable state of preservation, not faded or blurred with age; fact is they are brilliant as though written yesterday”. This is persuasive (compare the images of the Iturbide notes in Mexican Paper Money in contrast to those of the Tesorerías de la Nación from the same year) but ignores the fact that the notes were withdrawn within 100 days and many were never issued. Shlieker wanted to date the ink through Carbon-14 but was told this was impossible.

Shlieker sent his findings to the Institute of Paper Chemistry and on 9 July 1969 they replied “If the Imperial Iturbides were circulated, or valid, for only 100 days, it could be possible that all of the notes were printed on paper from a single supplier. It is likely also that there would be only one watermark. It is likely that the furnish (raw materials used to make the paper) is the same. If any records can be found to determine the supplier of the paper, or if it could be determined what the general source of paper for the Mexican Government in those days was, considerable information could perhaps be found that would have a quite convincing bearing on the question of the paper used. If the source of the paper, in view of the very short time that the notes were printed, could be determined, much time might be saved in providing valuable evidence for authentication of the notes.

The watermark you describe and the “horizontal lines” might also be very significant. The “horizontal lines” are very likely what we refer to as “chain lines.” These result from the construction of the screen, or wire, on which the paper was formed either in a hand mould or on a machine. Again, if you could get a note known to be authentic, details of both the watermark and the screen markings might provide a basis for authentication. The difference in distance between the “chain lines” and the watermarks and the situation of the deckle edges between the single note and the sheet of uncut notes you mention in your letter makes it difficult to believe they are both authentic.”

However, Shlieker’s argument about appearance was challenged by others, such as Carlos Gaytan, who paradoxically suggested that counterfeits were produced using paper from the era. “There are, all over Mexico, thousands of books on sale at the second hand stores, which were printed in the first half of the XIX Century; those books have, invariably, the first and the last leaf entirely without printing. Well, the forgers tear off those pages and use them to print their one and two peso Iturbides. So, the paper used in the forgeries is one hundred per cent genuine, that is, MORE OR LESS of the same quality of that used by the Imperial Iturbide Government. This MORE OR LESS may be our only way to differentiate genuine and fakes. Chemical and even Carbon 14 analysis would show the paper of the fakes to have been made on the first third of the XIX century. Beside the old book supply, anyone traveling through Mexico may go to small or large town communities, offer a few pesos to an underpaid clerk and get blank sheets from 1825 files. In conclusion, a very VERY close study of the paper used in the genuine notes is necessary in order to detect forgeries on the sole basis of the paper”. In a letter of 17 July 1969 Clyde Hubbard suggested that any investigation regarding the authenticity of these bills should be directed to a study of the inks used rather than the paper used. “The reason for this is quite obvious: old paper can be obtained in the files of Government offices, particularly in small towns or cities. This paper could be used for the counterfeiting.” Clyde Hubbard’s own notes came from old files in the City of Durango and there was no doubt in his mind about their being genuine.

Shlieker made an “infinitesimal” study of $1 10813 and $2 46607, offered at $360.00, the pair, “scrutinizing every detail, point by point in comparison with all records in catalogs. The only variation I can find is the 1° in the date. These two notes bear the same 1° in the date, whereas Gaytan’s catalog shows a more bold 1 on the Un Peso, not the same as on the Dos Pesos. … The diamonds (in the vertical designs) do not match those as shown in the catalog. Of course this may vary due to change in printing plates, but it seems to be a distinct pattern in this respect that is repetitive in these two notes, making it so obvious that they are copies. They are identical in this respect. … Another significant facet is that the 7 ends in a dot on the Un Peso, none shown in catalog. … The entire imprinting of all lettering on the Un Peso was done under heavy pressure as the reverse shows a deep deboss to the point of perforating. This is not true of the Dos Pesos which shows a normal imprint. The watermarks appear to me to be a key or prime factor in determining a genuine note.”

Later, on 16 August 1970, Shlieker wrote to Newman “At this time, I am not convinced as to what represents a true or false Iturbide. To me the physical appearance and observation of any note is not conclusive. The paper and printing can and could be identical, it is easily duplicated. To me the most important clue is the hand inscriptions on the notes, namely the serial number and endorsements (from Oaxaca). However all notes do not bear an endorsement. One point in question, and one of the most important to me, is the different styles of digits used in the serial numbers. Some are the old style of numbers and others are the modern day method of numbers, also I have seen some with a mixture of both? They all appear in sepia ink. Regarding endorsements, of which all mostly appear on the reverse; the latest word I have received from an avid colleague is that he observed and tested the ink on a four note sheet. He used a simple test of smudging or rubbing transferring to another sheet, the ink came off very easily. I would say not very conductive of inks this old, unless a clever counterfeit. All the other characteristics appeared as genuine The few notes I have on hand, I am still attempting to date the ink, They would be the serial number ink only as I do not have notes in my personal possession with endorsements.

The inherent characteristic of counterfeiting these notes is so vast that it may not be possible to establish a validity. … I would be more inclined to accept a single note without the endorsement properly watermarked and old style of numbering the serial number, as a genuine. However, style of numbers is yet to be determined as to which is old or modern, I have had many opinions on this, none conclusive.”

In January 1971 Rosovsky wrote his article “The Paper Money of Iturbide” for the Boletín Numismático, No. 70 (also available at the USMexNA online library) in which he was able to detail how the notes were printed at the rate of eight at a time, four on one side with blank reverse and four on the other half, but on the opposite face of the paper, so they also have a blank reverse. Each sheet of paper had its corresponding watermark distributed between two halves: in one, the name of the manufacturer ‘JHP ROMUGOSA’ under the trademark of its mill: a medieval tower with a big entrance door, called Tower of the Guarros, and laurel leaves, and in the other simply ‘No 1o’, undoubtedly referring to the paper quality. This paper, of Spanish origin, was bought at the important wholesale-retail store “El Comercio de Mexico”, owned by José Severo de Arana, and located at the Portal de las Flores, in the main square. Rosovsky’s article was supplemented by an article “Paper Money of Iturbide” by Alberto F. Pradeau (Boletín Numismático, No. 74, January-March 1972, also available at the USMexNA online library) which laid out a couple of the relevant decrees.

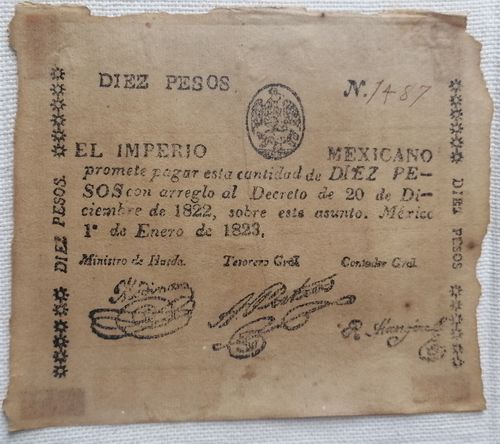

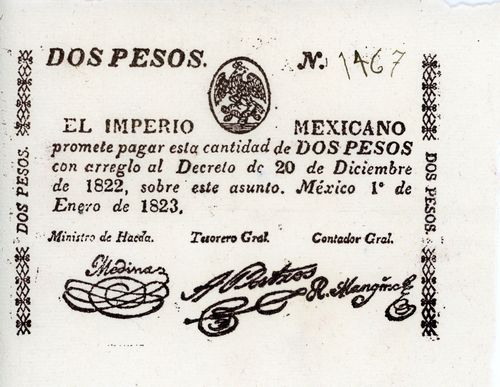

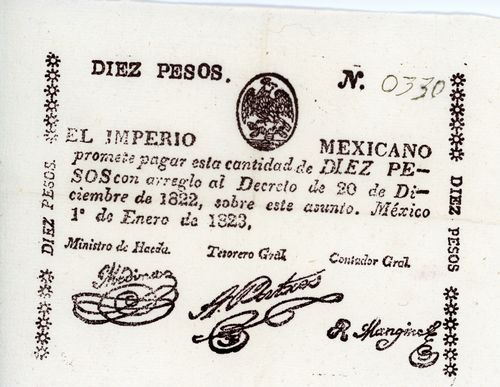

So what have we learnt about counterfeits? The consensus appears to have been that there were modern counterfeits produced in San Luis Potosí, as described by Tamborrel in his Boletín article, but that almost all of these had all been destroyed. The two examples pictured in in the article were

These counterfeits were done by an offset process whereas the authentic notes were printed by press and the impression on the reverse could be seen as the letters are slightly raised. The counterfeits were numbered by hand in sepia ink, in an attempt to copy the original but in the present day style rather in that of the nineteenth century.

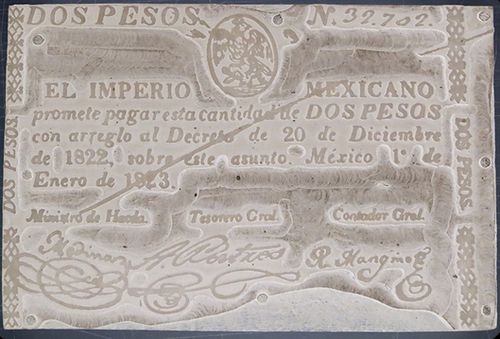

In May 1970 Rosovsky was pleased to send Newman such a counterfeit that he had managed to obtain, “a very scarce item, now, since all of them were promptly destroyed”. His specimen was made on a thicker paper, very little alike to the original Iturbide notes, with a watermark, partly seen as GABEL. “The paper came NOT from old books but from large leaves of old judiciary paper archives, more or less easy to obtain in the provincial towns. All these fake notes had the signatures on the same place since they were all copied from one and the same single, genuine Iturbide note and not stamped separately. Even the TWO pesos notes, then absolutely impossible to get, had been copied from the same ONE peso note, but with the ONE altered to TWO and an S added to the word “peso””.

Another $1 note from the correspondence, illustrated below, is clearly a forgery. It is also described as having as a watermarked CABEL below a coat of arms but this cannot be one of the San Luis Potosí forgeries as the right-hand signature is in a different place.

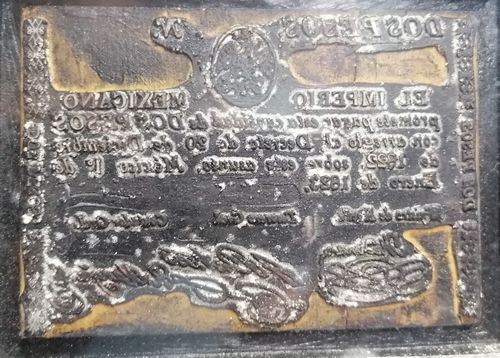

As for contemporary counterfeits, Rosovsky wrote “If they exist, they are very difficult to recognize because all are printed on original paper pertaining to the historical period of the First Empire of Mexico.” but he did managed to send Newman a “GENUINE COUNTERFEIT Iturbide TWO pesos note, counterfeit and cancelled in 1823; obverse half-crossed and on the reverse, the words hand— written: “NO VALE”. In response Newman wrote to Rosovsky “The counterfeit is of particular interest because it is apparently made in 1823. It seems to be made by engraving a plate by hand and then casting that plate in lead for printing purposes. The type on the normal notes is uniform while on the counterfeit each letter is different each time it is repeated. The alignment is very poor and indicates hand engraving of the base plate. The impression of the letters through the paper also confirms the fact that this was positive printing rather than engraving printing (intaglio).”

The notes illustrated in the correspondence include this $2, numbered 10109, as a genuine note

in contrast to this $2, numbered 28337, as a counterfeit.

and an undated memo lists two types of counterfeit $1 notes:

(1) Lettering crudely engraved and not typeset; base of ‘r’ in ‘Enero’ high; period after 1823 missing; capital ‘N’s in top row different in shape; ‘n’ in ‘cantidad’ tilts to the left; base of ‘to’ in ‘asunto’ high; and

(2) Offset printing; normal space omitted between ‘de’ and ‘1823’; the Tesorero Gral’s name is misspelt (‘Portxos’ (actually ‘Bartres’) instead of ‘Portxes’).

and one type of counterfeit $2 notes:

(1) Offset printing; normal space omitted between ‘de’ and ‘1823’; base of ‘al’ in ‘Contador Gral.’ much too high; on left border ‘OS’ in ‘DOS’ are upright and not slanting to the right as other letters; the Tesorero Gral’s name is misspelt (‘Portxos’ instead of ‘Portxes’)

Having reviewed the notes sold in recent Stack’s Bowers and Heritage auctions I noticed the following, sold by Heritage for $528 on 13 January 2020. This seems to have questionable type and and a misprint ‘Deereto’ for Decreto’.

I realise that anyone reading this article will have expected to learn how to recognise whether their Iturbide note was a counterfeit. I apologise if they feel short-changed, but hope that by recalling correspondence from 60 years ago and noting some recorded differences I have added something to the debate in this bicentennial year. I would be pleased to hear from anyone who believes they have a forgery.

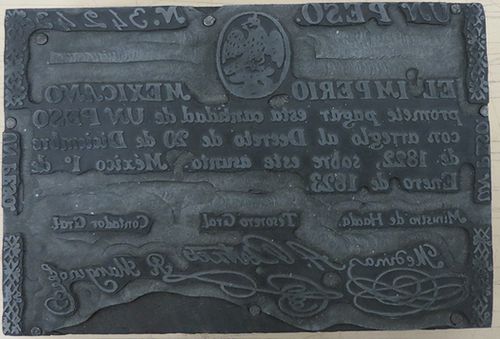

In response I received the following. Juan Pablo Mejia Gallegos wrote “My father, Jorgé Mejia, has been a collector of Mexican coins for a few decades, and we have three rubber stamps, which I think were bought in Guadalajara. These stamps and the prints they produced, all nicely framed, have probably been in our family’s possession for over twenty years.”

Cory Frampton wrote: “I have in my collection of Iturbide notes an example of each denomination that is decidedly counterfeit. They were bought at a show in Guadalajara in October 1997, and the seller claimed that they had been made using paper taken from old books, just as Clyde Hubbard recounted.

They each have part of a watermark but these are hard to decipher. The $1 has what may be a cup, the $2 has a name including RRER and the $10 has the letters ALVA at the base of some symbol.

The obvious indications that they are countefeit are the size and manner of the serial numbers. Also, the $1 has ‘de1823’ in place of ‘de 1823’.

Cedrian López-Bosch added “Just to let you know that in the Banco de México’s collection are two plates for a $1 and $2 Iturbide note (#233 and #234). The $1 plate is now on permanent display in the bank’s museum at Avenida 5 de Mayo 2, in the centre of Mexico City. When the images are flipped and the colour inverted it is easy to see that they include the signatures (which were added separately on the genuine notes) and also a serial number. I doubt if these plates were ever used."