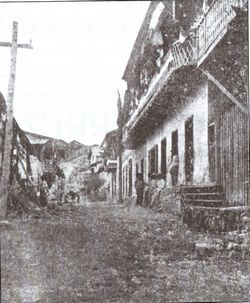

Pinos Altos (in 1991, now destroyed)

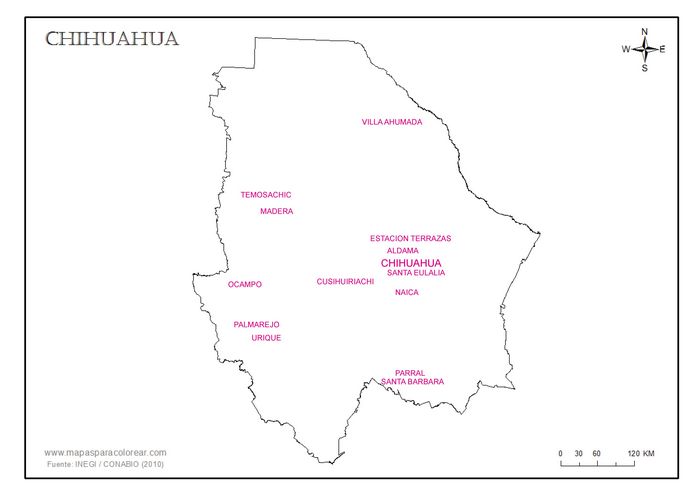

Pinos Altos is on a mountain top about fifteen miles north of Jesús María (now Ocampo). Now it is easily reached from the Chihuahua-Sonora highway west of Basaseachic but as the new owners have stripped away the hillside there is no longer much to see.

In 1877 the mines were sold by their Mexican owners to the Anglo-American Negociación de Pinos Altos (or Compañía Minera de Pinos Altos) headed by John Buchan Hepburn. Hepburn paid $100,000 for the property and spent even more on establishing a hacienda de beneficio and opening up the mines.

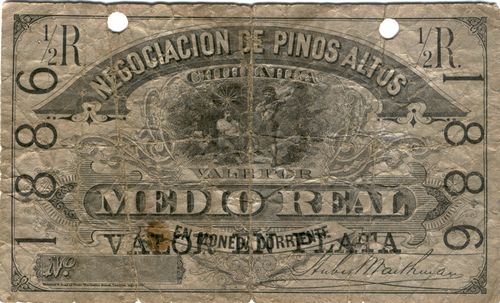

Hepburn kept an account with the Banco Mexicano and every month brought in as much paper money and hard cash as he thought necessary. However, occasionally the notes ‘ran out’ before the stage arrived and at other times it was necessary to delay the stage. At these times Hepburn, who had the only store in Pinos Altos, did not have enough notes to pay his accounts, so he decided to issue his own paper. These were redeemed periodically, at par, with Banco Mexicano notes when the stage arrived from Chihuahua. The amount in circulation fluctuated between $40,000 and $50,000.

main street and tienda de raya, Pinos Altos

At some time (in 1882 or 1883 according to Enrique Creel’s reminiscence in 1920 but probably earlier{footnote}Otherwise, the timetable is too tight. However, Pinos Altos seemed particularly susceptible to fire as the entire business section was destroyed by a fire, started when a lamp overturned in a casa comercial, on 29 May 1884 (La Libertad, 17 June 1884 list twenty-one businesses, besides the company's tienda de raya, that lost all their stock, and states that the population either fled to the hills or started pillaging; Cleveland Plain Dealer, 17 June 1884) whilst in January 1885 a Dallas newspaper reported that the whole of Pinos Altos had been destroyed by fire and hundreds made homeless (Dallas Weekly Herald, 15 January 1885). This cannot have been the same fire as by that time Hepburn was dead.{/footnote}) a fierce fire, whipped up by a strong wind, destroyed almost the whole of Pinos Altos. People lost everything, including, it was thought, any paper money and the idea spread that the company was responsible for its issue and should make good any loss in its notes by sharing out $40,000 amongst the employees. Hepburn was a considerate man, offering to reconstruct the houses, helping to replace food and clothing and willing to compensate for any notes that had been burnt, but he did not want to pay out twice on his notes so he arranged for a shipment of $50,000 in Banco Mexicano notes from Chihuahua and announced a period of sixty days in which the Pinos Altos notes would be redeemed. After that time the notes would be demonetised, and any sum outstanding would be shared out amongst people who were thought to have lost notes.

After a few days’ vacillation people began to present their notes for redemption and to everyone’s surprise over 99% of the notes in issue were exchanged for Banco Mexicano notes. It seemed that as soon as the fire started people made sure that their notes were safe, some mothers even putting this before looking after their own children{footnote}CEHM, Fondo Creel, 238, 60996 letter of Enrique C. Creel, 9 March 1920{/footnote}.

In January 1883, Hepburn decided to change the workers' pay period from the customary week to a less convenient fortnight, and, to make matters worse, decided that they should be paid half in cash and half in store-coupons. The workers called a strike and staged a demonstration in the camp's main street, where a worker and a company guard became involved in a fight in which both died. As the only local authority, the town judge ordered a dozen men to take up arms and restore peace. Outnumbered, these were soon overpowered by the strikers, who quickly moved on to the company's headquarters. However, after an exchange of gunfire, the strikers retreated to the company store, taking it, and barricading themselves inside. When Hepburn stepped out onto the balcony of the local hotel to address some of the miners, a shot rang out and he fell over dead, landing in the street below.

When news reached Jesús María, Carlos Conant, Superintendent of the Santa Juliana Mining Company and jefe político of Jesús María, rode to Pinos Altos at the head of twenty-six men and declared martial law. A summary court martial then sentenced three men said to have been responsible for starting the disturbance to be executed on the spot. By nightfall, Ramón Campos, jefe político for the Rayón district, had instructed Francisco Armenta, of Uruachic, to ride into Pinos Altos with some men and officially patrol the area. By the time he got there, two more had been shot to death in retaliation for Hepburn's death. Sixty-eight others were later sentenced to forced labour. Those shot ‘were the first victims suffered by the labour movement in the Americas’{footnote}Gastón García Cantú, El socialismo en México, Siglo XIX, México, 1969{/footnote}, as these events happened three years before the Haymarket massacre in Chicago.

On 28 January 1891 a Scotsman, Cornelio Callahan, with an escort of fifteen men, was conducting 45,000 pesos in silver coinage and banknotes (billetes) to Pinos Altos to pay wages and salaries when he was attacked at Las Manzanillas by sixteen men. These bandits were repulsed and subsequently tracked down{footnote}Francisco Almada, Apuntes Históricos de la Región de Chínipas, Chihuahua, 1937{/footnote}.

As said above, the company seems to have been particularly susceptible to fire. In June 1895 it was reported that fire originating from spontaneous combustion had destroyed the stables, hoist works and office, including all its books and $16,000 in Mexican paper money{footnote}The Journal Times, Racine, Wisconsin, 21 June 1895{/footnote}.

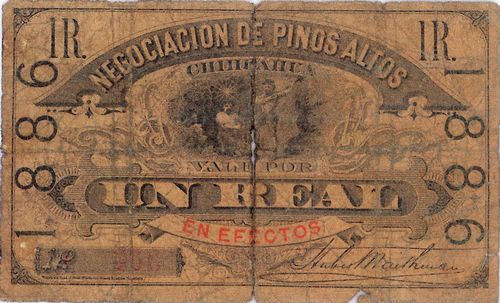

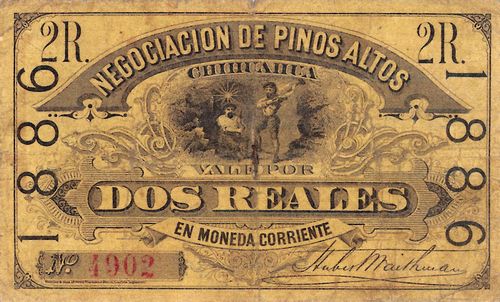

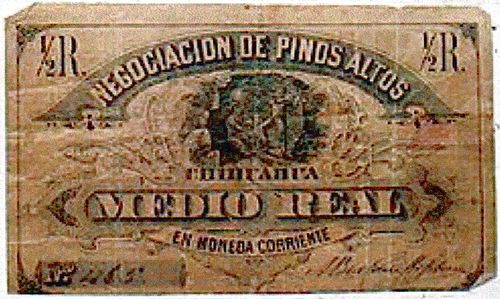

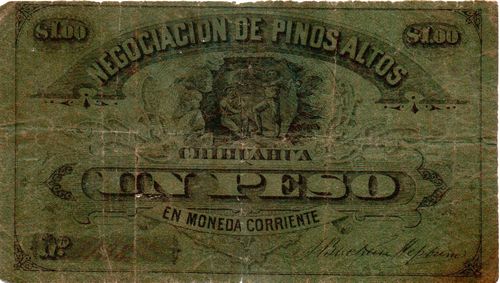

Four denominations are known from the company and surviving examples could help to recreate the chronological sequence of the issues.

The pre-fire notes (i.e. before 1882/1883) may have been of a different type, but if the company reused the same design they must have distinguished the new issue in some way, perhaps through a different signatory or overprinting a date.

The surviving notes are of two different designs. One set was produced by the printers Waterlow and Sons, of 14, Great Winchester Street, London, England{footnote}Waterlow and Sons Limited was a major worldwide engraver of currency, postage stamps, stocks and bond certificates. It originated from the business of James Waterlow, who began producing lithographic copies of legal documents at Birchin Lane in London in 1810. The company gradually grew; it began printing stamps in 1852, and Waterlow's sons Alfred, Walter, Sydney and Albert joined the business. James Waterlow died in 1876, and the company became a limited-liability company. In 1877, due to a family dispute, Alfred, the eldest son, and his sons and Alfred Thomas Layton, formed Waterlow Bros. & Layton retaining the Birchin Lane premises. The other brothers, under the Managing Directorship of Sir Sydney (as he had become after being Lord Mayor of London in 1872) continued Waterlow & Sons Limited), operating from London Wall, Finsbury Market and other factories. In 1887, on the death of Alfred, Waterlow Bros & Layton became a company. The two companies later reunited in 1920.

Waterlow and Sons has limited success in Mexico but in 1910 and 1913 their agent, Mr. Bass, was actively seeking business from the Banco Nacional de México and the Banco de Londres y México and thus break the American Bank Note Company’s monopoly.

Waterlow Bros. & Layton produced scrip for the El Progeso mining company at El Triumfo, Baja California.{/footnote}. A ½ real payable en moneda corriente but overprinted ‘silver’ (valor en plata), a one real in coin (en efectos) and two reales (en moneda corriente) are overprinted with the date 1886, and signed by Hubert Waithmann.

Another series had no printer's imprint and was no doubt produced locally.

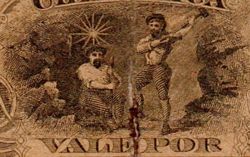

'CHIHUAHUA' now appears below the vignette, instead of the text 'VALE POR' but, more significantly, the vignette of the two miners is a poor imitation of the original vignette.

These half real and one peso notes payable in copper coin (en moneda corriente) are signed by Hepburn and so must date to before 1883. On the assumption that the better quality issue would be the earliest, i.e. also before 1883, was this issue a response to a (temporary) shortage of notes?

| date on note | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| ½r | EN MONEDA CORRIENTE | |||||

| 1886 | EN MONEDA CORRIENTE o/p VALOR EN PLATA includes numbers 1285 and 4195 |

|||||

| 1r | EN MONEDA CORRIENTE | |||||

| 1886 | EN EFECTOS includes number 366 |

|||||

| 2r | EN MONEDA CORRIENTE | |||||

| 1886 | EN MONEDA CORRIENTE includes number 4902 |

| date on note | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| ½r | EN MONEDA CORRIENTE includes number 465 |

|||||

| $1 | EN MONEDA CORRIENTE includes number 438 |

The signatories are:

|

John George Buchan-Hepburn was born in Smeaton, Scotland on 24 September 1841, the son of Sir Thomas Buchan-Hepburn of Smeaton Hepburn, 3rd Baronet, and Helen Little{footnote}information courtesy of Michael Snelgrove{/footnote}. He was for several years a subaltern in the 9th Lancers and was quartered with that regiment at Aldershot in 1861, and at Brighton in 1862-1863. He sold out of the 9th Lancers in 1863{footnote}West Surrey Times, 24 February 1883{/footnote}. As detailed above, he bought the Pinos Altos mine in 1877 and died on 21 January 1883, shot during a protest. |

|

|

Huberto Waithman: Hubert Waithman was born in England (probably Chorlton, Manchester) on 18 March 1859, to a prominent Quaker family. In 1879 Hubert’s father, Joseph Waithman, John George Buchan-Hepburn, and W. M. Kerr and the Pinos Altos (Mexico) Mining Company Limited made an agreement to acquire the business, mining rights, machinery, etc and “to do all acts necessary for obtaining for the company a legal status in Mexico, or any country in which business may be carried on.” Hubert married Grace Gertrude Winton on 14 December 1887 in Oakland, California and their three children, Joseph deLindeth Waithman, Maude Victoria Waithman and Grace Elizabeth Waithman, were born in Pinos Altos but after Hubert’s death in 1891 their mother took them to live in Hayward, California{footnote}Information courtesy of Michael Snelgrove. Waithman’s descendants say that he “was shot by bandits near the silver mines", but in a letter, Enrique C. Creel records that he committed suicide at Pinos Altos when his wife discovered that he was having an affair (CEHM, Fondo Creel, [ ], 66088){/footnote}. |

|

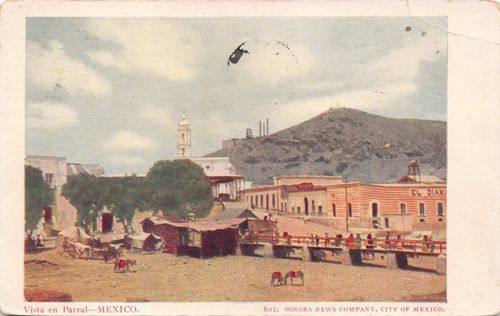

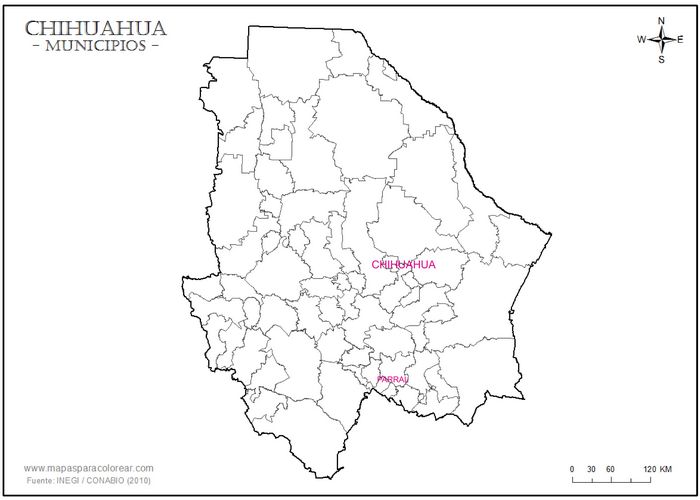

Valle de Zaragoza is a municipality 70 kilometres north of Hidalgo del Parral. Founded in 1866, the Bellavista yarn and fabric manufacturing company became the main one during the Porfirian era within the state of Chihuahua.

In March 1878, on the orders of the state government the Juez 2º de Paz, Ignacio Herrera, carried out an investigation into this Fábrica de Tejidos Bellavista. He reported that all the witnesses said they were paid en efectivo, with no obligation, though there was a tienda de raya, but that it was well stocked and the prices low{footnote}AMP, Justicia, Juez de Paz, Laboral, caja 30, exp. 19{/footnote}. However, the governor, on 12 May 1878, instructed the Presidente Municipal to ensure that the company paid in legal tender and that the tienda de raya carried goods of good quality at normal prices.

In August of the next year the Presidente Municipal received a complaint from the factory’s workers that the factory had been closed, that prices were higher than anywhere else in the world, and the tienda de raya did not stock the essentials of life. The only money in circulation were some chits (voletos anónimos) from Jacobo Muncharras and his sister Doña Arcádia to buy the things that were not in the tienda de raya. The complainants asked that the company be forced to adhere to the previous instructions; that any notes (billetes) that the company issued in payment or as advances were signed and guaranteed by the company or manager and conformed with Angel Trías' law of 11 December 1878, so as to be freely accepted in the marketplace, and that the company be punished for issuing anonymous chits (billetes anónimos) which it refused to recognise.

On 14 August the Presidente Municipal again ordered the company to pay its workers in legal tender and asked the Juez 2º to investigate the anonymous chits and proceed accordingly. The judge’s report stated that the factory had been stopped for more or less three months for lack of cotton; that as a consequence it had issued some chits (voletos) for goods from the Establecimiento Mercantil de Buena Vista, but when people had used them to buy goods in other establishments the company had refused to honour them. One such note read “B. Vista Agosto 11 de 79 = Descontar = Francisca Rojas = Recibira dos pesos = 16ñ” without any signature whilst another read “ = Bella Vista = Agosto 11 de 79. = Descontar = Conrada Legarreta = Dos pesos = 16ñ“, again without a signature{footnote}AMP, Justicia, Juez de Paz, Laboral, caja 30, exp. 25{/footnote}.

By 23 August Jacobo Muncharras was willing to make arrangements but still had not paid in efectivo{footnote}AMP, ibid. letter 2124 from Secretario de Gobierno, Chihuahua to Presidente Municipal, Valle de Zaragoza, 23 August 1879{/footnote} and the matter was passed to the relevant Juez{footnote}AMP, ibid. letter Presidente Municipal to Secretario de Gobierno, Chihuahua, 3 September 1879{/footnote}.

However, in 1880 problems arose between the owners and their 18 weavers{footnote}Periódico Oficial, 10 April 1880{/footnote}. Within a month, the Administración de Rentas del Estado decreed an embargo against the company for not having complied with the payment of their direct tax. In 1881 Doña Arcadia, her sons and her partner, Francisco E. Franco, petitioned Tomás Macmanus and Sons who took charge of everything related to put the factory up for sale. The Macmanus, in turn, granted special power to Adolf Iwonsky to sell Bellavista for $160,000 pesos, It is likely that part of the company was acquired at that time by Federico Sisniega. In 1909, the mezclilla denim out of Bellavista would have a value of 150 thousand pesos per year and the wages paid there were 1.25 pesos a day{footnote}Anuario, 1909{/footnote}.

In September 1878 P. Bustamante, of Chihuahua, applied to the Supreme Court for an amparo concerning an issue of vales al portador. He was denied, because the law had to intervene in credit establishments{footnote}Ignacio Luis Vallarta, Archivo Inedito, Relación de Amparos Notables fallados por la Suprema Corte de 1878-1879, No. 357{/footnote}.

The actual text is needed to show to what this refers. It could be a case of an establishment paying its workers or of a casa comercial issuing higher value vales al portador for use in business transactions, along the line of the vales al portador in Yucatán.

On 30 November 1889 President Porfirio Díaz banned the use of tokens and similar devices after 1 July 1890 and the monetary reforms of 1905 again prohibited their use and supposedly led to their withdrawal but thereafter there were numerous examples of private issues. During the first decade of the new century Silvestre Terrazas' newspaper El Correo de Chihuahua constantly campaigned against the practice of company stores (tiendas de raya) and the state government on several occasions, on 19 June 1905{footnote}Periódico Oficial, Año XXV, Núm. 38, 22 June 1905{/footnote}, on 18 September 1908{footnote}Periódico Oficial, , 20 September 1908; Chihuahua Enterprise, 26 September 1908{/footnote} and 30 March 1909{footnote}Periódico Oficial, , 8 April 1909{/footnote} issued circulars to the jefes políticos instructing them be more vigilant and strict in seeing that corporations and business concerns did not violate the law and to report infringements to the governor.

On 30 November 1889 President Porfirio Díaz banned the use of tokens and similar devices after 1 July 1890 and the monetary reforms of 1905 again prohibited their use and supposedly led to their withdrawal but thereafter there were numerous examples of private issues. During the first decade of the new century Silvestre Terrazas' newspaper El Correo de Chihuahua constantly campaigned against the practice of company stores (tiendas de raya) and the state government on several occasions, on 19 June 1905{footnote}Periódico Oficial, Año XXV, Núm. 38, 22 June 1905{/footnote}, on 18 September 1908{footnote}Periódico Oficial, , 20 September 1908; Chihuahua Enterprise, 26 September 1908{/footnote} and 30 March 1909{footnote}Periódico Oficial, , 8 April 1909{/footnote} issued circulars to the jefes políticos instructing them be more vigilant and strict in seeing that corporations and business concerns did not violate the law and to report infringements to the governor.

In 1905 a company was fined 500 pesos for using scrip and El Correo de Chihuahua warned other companies to give up the practice. Some firms, it said, issued boletos because of a shortage of fractional currency whilst others were not content with that but also imposed a charge of 10 to 15 per cent to cash their scrip{footnote}El Correo de Chihuahua, 2 December 1905{/footnote}. In 1908 the Chihuahua Enterprise reported that some companies had recently violated the law and that the federal government had fined them to the limit{footnote}Chihuahua Enterprise, 26 September 1908{/footnote}.

Although apart from La República (infra) no notes remain from this period there are several other references.

In October 1911 it was reported that Luis Terrazas was paying the workers on his hacienda at Villa Ahumada fifty centavos a day, not in cash but in vales{footnote}El Correo de Chihuahua, 10 October 1911. Worthington, op. cit., lists a trade token for the Hacienda de Encinillas: TIENDA DE RAYA / CHIHUAHUA / MEX. / ENCINILLAS BUENO POR / $1.00 / MERCANCIAS{/footnote}.

In March 1908 the Chihuahua weekly, El Universo, reported on the dire situation in Madera, where work had dried up. Even worse was that the company paid its workers with vales, which were used to buy goods in the company’s stores at exorbitant prices. If the workers managed to exchange their vales for hard cash, they only received 50% of their nominal value. Many of the workers had been tempted to Madera by the thought of the good wages that were paid there, but now found that they had to stay because they lacked the means to leave. El Universo thought that, as payment in vales was illegal, the authorities should intervene and put a stop to the practice{footnote}El Universo, 22 March 1908{/footnote}.

In August 1908 the company closed down all its operations and posted a notice that it would pay only 20% of the wages it owed, in cheques drawn on the Banco de Sonora in Ciudad Chihuahua. Troops were called in to counter any disturbances{footnote}El Correo de Chihuahua, 3 August 1908{/footnote}. In September 1908 President Díaz imposed on the Sierra Madre Land Lumber Company a fine for issuing vales ó boletos[image needed] similar to that imposed on the Greene Gold Silver Company (infra). The company had put more than $20,000 in these boletos into circulation{footnote}La Patria, 19 September 1908{/footnote}. Presumably this refers to the same company,

On 14 June 1911 the employees of the Compañia de Madera petitioned Governor González over the system of chits (boletos or tiquetes) usable only in the tienda de raya or butcher's shop, the high prices, poor quality and lack of goods. Payment had originally been made on a daily basis but had changed to monthly because of the disruption to railway traffic. Now that the trains had resumed, the company had not reverted to the earlier practice because of the benefits of the new system{footnote}El Correo de Chihuahua, 24 June 1911{/footnote}. Within a few days the company and its employees resolved their differences: the management began paying wages in cash, daily instead of weekly in the workshops and weekly instead of monthly in the sawmills, and reduced prices in the company store to match those in the capital{footnote}El Correo de Chihuahua, 20 June 1911: 26 June 1911: 15 July 1911. Almada (Vida, proceso y muerte de Abraham González, Mexico, 1967) mentions a a strike in July 1911 at the Anglo-American Madera Lumber Company, because of the tienda de raya and the fact that the company had given the Chinese a monopoly over the sale of fruit and vegetables. González gave instructions that the company cover their wages in cash (en efectivo), and allow employees to shop at the tienda de raya, if it was in their interests, or at any of the other establishments. This might refer to the same dispute{/footnote}.

This company was one of those owned by the American entrepreneur William Cornell Greene. Greene received his first concessions in 1902 and in March 1906 was granted a concession to establish a processing plant in Concheño and to run a railway from Guerrero to Rayón and a road from Temósachic to Concheño. In April 1907 the company was granted a further concession for mines, processing plants, electric plants, roads, sueldos de empleados and tiendas de raya in the districts of Galeana, Guerrero and Rayón.

Almada{footnote}Francisco R. Almada, Apuntes Históricos del Cantón Rayón, Chihuahua, 1943{/footnote} states that after Greene was bankrupted in 1908 the company had trouble payings its wages. After the local jefe político, Profesor José María Rentería, reconciled the parties, the company paid a percentage of the outstanding wages in cash and the rest in goods from the tienda de raya, which third parties bought off the workers for three-quarters of their value.

In September 1908 the Greene Gold-Silver Company was fined the maximum possible by the Secretaría de Hacienda for using a libreta to pay its workers{footnote}El Imparcial; La Gaceta de Guadalajara, 6 September 1908. Another description in La Iberia, 6 September 1908 and El Diario, 7 September 1908 said the fine was for using vales o cheques por mercancias to pay its workers in Ocampo and Concheño{/footnote}, though the wording had been drafted by the Secretario or Sub-secretario de Hacienda in Mexico City to comply as far as possible with the law{footnote}ACCCC, folder 5, letter from Young to L. D. Ricketts, 8 September 1908{/footnote}. This might have been as a result of El Universo’s report.

No notes are known to exist though specimens for coupons used in the tienda de raya of Greene's Cananea Consolidated Copper Company in neighbouring Sonora are known (see Cananea).

The Chihuahua Lumber Company established the first mechanised sawmill in the state at San Juanito, Bocoyna.

In September 1908 President Díaz imposed a fine of $250 on the company for using vales-tarjetas[image needed] to pay the workers in the sawmill at Cuesta Prieta{footnote}El Tiempo, Año XXVI, Núm. [ ]74, 25 September 1908{/footnote}.

In January 1909 the Negociación Minera de Rio Tinto, Estación Terrazas, about 60 kilometres from the state capital, was reported to be paying their workers with vales{footnote}El Correo de Chihuahua, 6 January 1909{/footnote}. Two months later another newspaper claimed that more than 200 workers at the mine were victims of the predations of the owner of the tienda de raya, who operated with boletas during the month and charged extortionate prices so that on payday the workers did not receive a centavo but remained in debt{footnote}El Pais, Mexico, 20 March 1909{/footnote}.

In 1908 at the foreign-owned La Gloria mine, in Placer de Santo Domingo, Aldama, about 60 kilometres north-east of Ciudad Chihuahua, the supervisor paid the workers with chits (cartas ordenes) drawn on an American, resident in the Hotel Robinson, Chihuahua. These chits did not carry the legally required counterstamp (marca) {footnote}El Correo de Chihuahua, 11 July 1908{/footnote}.

El Correo de Chihuahua originally claimed that at the Las Plomosas mine, Aldama, they had the same system of chits as La Gloria and, because of the economic crisis, workers had not been paid for three months{footnote}El Correo de Chihuahua, 11 July 1908{/footnote}. However, a fortnight later the paper ran a retraction: it said that it had been informed that the miners were well treated and well paid, not in vales but in cash, and were not obliged to make their purchases in the company’s tienda de raya{footnote}El Correo de Chihuahua, 26 July 1908{/footnote}. So that’s alright, then.

In 1906 three hundred miners in Santa Eulalia petitioned the state government to stop their companies giving them chits (vales) to be used in specified stores because of the high prices that these stores charged. By September, as a result, they no longer had to buy their goods at the tiendas de raya and their lifestyle improved as a consequence{footnote}El Correo de Chihuahua, 10 September 1906{/footnote}.

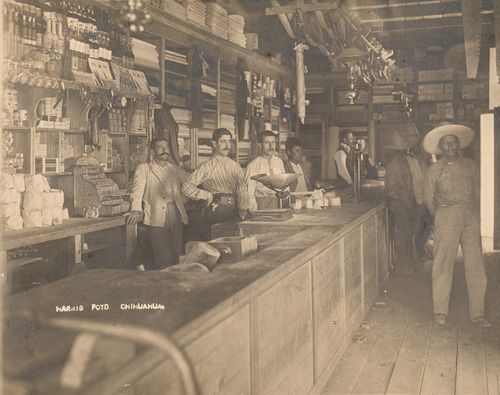

José de Stefano (wearing the striped shirt} in the Tienda La Bella Napoli, 1910

(courtesy La Fototeca del Centro INAH)

Naica is a mining community about 22 miles south of Delicias in south-east Chihuahua. In 1910 it had two thousand inhabitants, mostly employees of the Compañías Explotadora de Naica, Compañia Minera de Lepanto, Compañia Minera de Naica and the Mighty Mountain Mining Company.

The Italian Jose de Stephano listed himself as a miner and merchant in the 1910 Album del Centenario. As a miner, he was president of the Compañía Minera de Lepanto (and Chihuahua representative for the Compañía Minera Fundidora y Afinadora de Monterey){footnote}The Mexican Herald, 22 January 1908{/footnote} and as a merchant, owner of the wholesale and retail store "Tienda Lepanto", which employed six staff{footnote}Anuario Estadístico del Estado de Chihuahua, 1909{/footnote}, no doubt the same as the "Tienda La bella Napoli".

In 1909 the Secretaría de Hacienda fined de Stefano five hundred pesos for using various ‘papeles ó tarjetas’[image needed] with a fixed value in his store{footnote}El Diario, 29 July 1909{/footnote}. Another newspaper described his system as ‘unos formularios, tarjetas ó libretas’{footnote}El Diario del Hogar, 28 July 1909{/footnote}. Stefano certainly used metal tokens but he seems also to have issued paper notes.

An American company was organised in Naica about 1903 and built its own narrow gauge railway from the Conchos station to the mine 20 miles away. In July 1911 the miners went on strike against the system of tickets (boletos) and deductions for non-existent medical facilities. The strike was settled through the intervention of Governor Abraham González{footnote}El Correo de Chihuahua, 24 June 1911: 16 July 1911{/footnote}.

The Cusi Mexicana Mining Company was organised on 27 July 1911 and in 1912 bought the properties that had originally belonged to Herrera, González, Salazar y Compañia{footnote}The properties had passed from Herrera, González, Salazar y Compañía to the Cusi Silver Mining Company in 1880, then to the don Enrique Mining Company (major shareholder Enrique Müller) in 1890, then Banco Minero in 1896 and finally the Helena Mining Company{/footnote}. Almada{footnote}Francisco Almada, Resumen de Historia del Estado de Chihuahua, Mexico, 1955. Worthington, op. cit., lists tokens: TIENDA DE RAYA / M. Co. / COSIHUIRIACHIC 1880 / 2 / REALES EN EFECTOS and the same design for 1/4, 1/2, 1 and 4 reales and 1 peso.{/footnote} mentions it as one of the companies that issued vales.

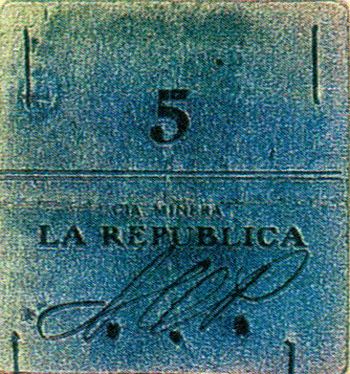

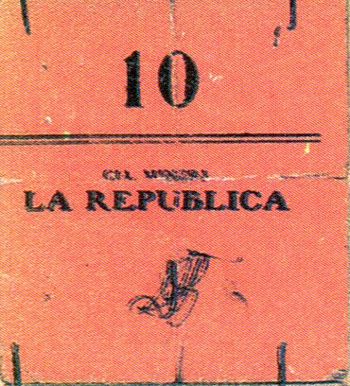

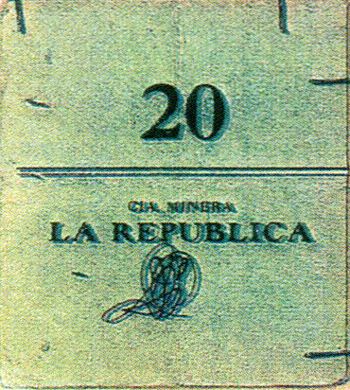

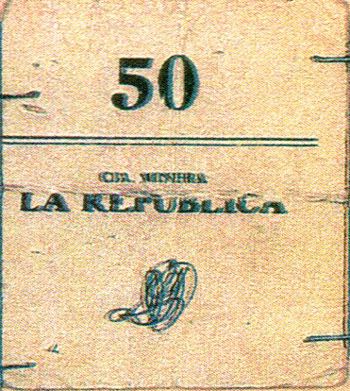

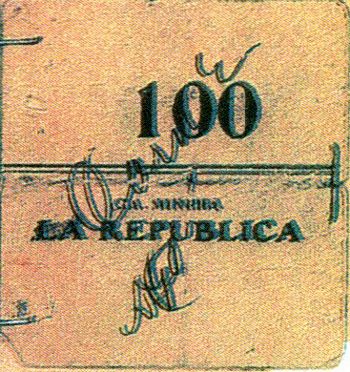

This mine was located in the district of Rayón, halfway between Ocampo (Jesús María) and La Bufa. It was discovered by a local miner, Manuel Amado, in 1894, who sold it to three gentleman, Gibbs, White and Alexander, from Miñaca. They in turn sold it to La República Mining Company, a company with a capital of $2,250,000 with the majority of shareholders from El Paso, Texas and Kansas City, Missouri, and its general offices in El Paso. In 1907 the general manager was M. B. Parker, from El Paso, who had been with the company since its inception{footnote}Federico García y Alva, Album-Directorio del Estado de Sonora, 1905-1907, Hermosillo{/footnote}. J. J. Mundy was President and B. F. Darbyshire Secretary{footnote}{/footnote}.

This company issued vouchers in at least five denominations – five (blue), ten (orange), twenty (green), fifty (beige) and one hundred (ochre) centavos. The 5c and 100c measure 60mm x 57mm whilst the other three values measure 64mm x 58mm. There are three different intials and the $1 note has 'carne' written on it.

| M. B. Parker, from El Paso, was the general manger from the company's inception. |  |

|

|

|

In 1908 the company was reported to the state government and on 2 October 1908 Secretario Guillermo Porras told the local authorities to apply the fine set by article 26 of the 1905 Monetary Law{footnote}Luis Gómez Wulschner, Pre-Revolutionary vouchers of the mining company “La Republica”. A Numismatic Discovery in USMexNA Journal , September 2004{/footnote}.

In his report on local administration in 1908 the jefe político of Ocampo, José María Rentería, reported that various mining and mercantile companies had issued scrip (vales, bilimbiques y boletos) in place of using legal tender and that he had imposed some fines to halt the practice{footnote}Francisco Almada, Apuntes Historicos del cantón Rayón, Mexico, 1943{/footnote}.

In November 1905 it was reported that the Palmarejo mine had abandoned the practice of paying with coupons for meat (boletos de 400 gramos carne)[image needed]. If workers earned 50 centavos they were now paid in cash, whereas previously they had to earn five pesos before they were paid in cash. Some said that Don Reinaldo (Almada?) had stopped the practice, whilst others attributed it to the new manager{footnote}El Correo de Chihuahua, 9 November 1905{/footnote}.

In August 1911 a correspondent, Federico Aguilar, reported to El Correo de Chihuahua on the situation in Urique. The mine there had been under the control of an American, H. S. Durand, who paid workers in cash, but in April 1911 Alfredo S. Monge, an associate of Becerra, the local cacique, had bought the mine and began paying in merchandise, using a system of vales or boletos[images needed]. The correspondent hoped that once governor Abraham González learnt of this, he would put a stop to such illegal practices{footnote}El Correo de Chihuahua, 20 August 1911{/footnote}.

In Santa Bárbara the American-owned Moctezuma Lead Company issued its workers with boletas for use in the company store{footnote}El Diario del Hogar, 22 January 1902{/footnote}. One such boleta was of red cardboard, measuring 12 by 7 centimetres. Along the top were ten little boxes with the numeral ‘5’ in each; along the bottom another ten with the numeral ‘1’; at the left five boxes with the numeral ‘10’ and at the right five with the numeral ‘2’{footnote}compare a similar system of 'tick offs' on the Cananea notes. If the description is correct, the notes would have been for $1.20, so the description is probably wrong.{/footnote}. In the centre was the legend:

G

Montezuma Lead Company.

Boleta de identificación en la comisaría para empleados de la compañía.

No es negociable.

Ni se reconocerá esta boleta sino cuando se presente íntegra y por el empleado á quien se expida.

Nombre del empleado .............

Macared, rayador en jefe.

In Santa Bárbara, the Compañía de Minas de Tecolotes y Anexas maintained production despite the economic crisis and did not have either its own tienda de raya or arrangement with any casa comercial but paid regularly on paydays in cash. However, a certain employee of the company did make loans to the workers (at a interest rate of 10% per week) and issued vales for his grocery store, cantina and billiard palour. Anyone who did not accept his vales lost their job{footnote}El Correo de Chihuahua, 11 February 1909: El Diario, 15 February 1909{/footnote}.

From 1907 many of the mines in Minas Nuevas (now Villa Escobedo), slightly north of Hidalgo del Parral, closed, with the exception of the “Veta Grande y Anexas”. In 1909 this mine was late in paying, and gave out boletos to be to be used in the expensive tienda de raya. Since the workers were receiving only a few centavos on paydays, the other shops in the area suffered and many closed, to the detriment of the local tax base{footnote}El Correo de Chihuahua, 2 March 1909{/footnote}.

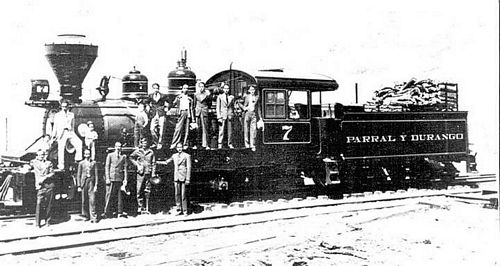

The Parral and Durango Rail Road Company was incorporated in Colorado in 1898 and owned the line from Minas Nuevas, Chihuahua to Paraje Seco, Durango, built under a concession granted on 29 June 1898. From Rincón it had a narrow gauge branch line to Parral, which connected with the Parral branch of the Mexican Central Railroad.

On 5 April 1912 the Orozquistas attacked the town of Parral. The Parral and Durango Railroad paid all the wages due for March in cash, being obliged to resort to many subterfuges in order to obtain and pay out the money but, as there were no longer any banking facilities in the town, it posted up notices[text needed] that wages from 1 April would be paid only by orders convertible into cash when normal conditions returned, or in merchandise. All the men without exception agreed to stay on{footnote}SD papers, 812.00/3706 letter 8 April 1912{/footnote}.

In April 1912 the Alvarado Mining & Milling Company took the same step as the Parral & Durango Railroad and posted identical notices[text needed]{footnote}SD papers, 812.00/3706 letter 8 April 1912{/footnote}.

In May 1911 Governor Abraham González ordered railroad contractor J. B. Chandler, of Kilometre 88, Ferrocarril Noroeste de México, to stop paying his employees with cardboard tokens (cheques de cartón) and henceforth to pay them in cash{footnote}Periódico Oficial del Gobierno Provisional de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, Num. 2, Ciudad Juárez, 25 May 1911{/footnote}.

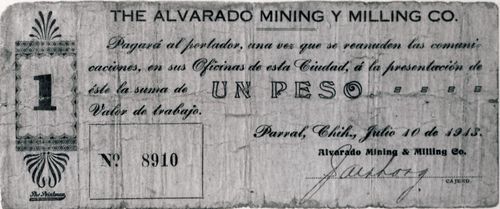

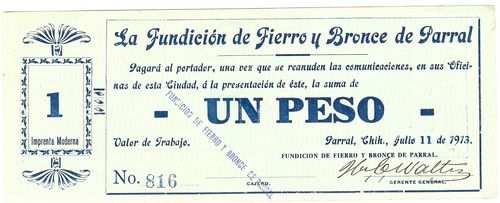

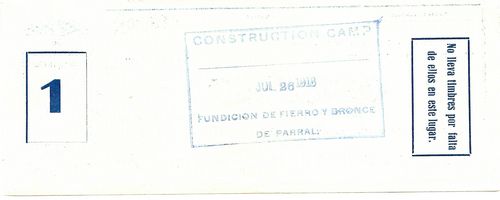

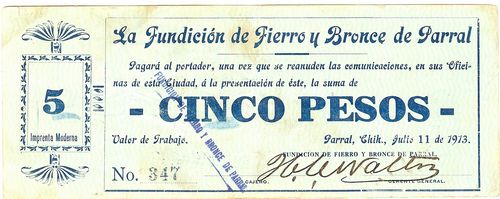

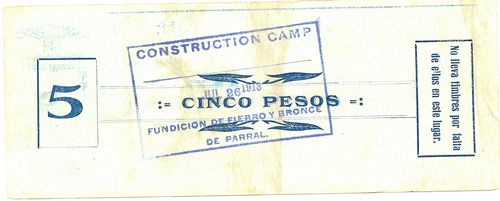

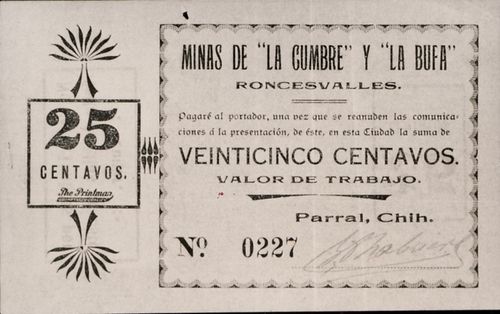

In the middle of 1913, because of the disruption in communications and the scacity of small change, certain companies in Parral and the surrounding area began to issue their own fractional paper currency. These valores de trabajo were payable to the bearer on presentation in the company's offices as soon as communications were restored (al portador una vez que se reanuden las comunicaciones, en sus oficinas de esta ciudad, á la presentación de esto).

Many businesses and individuals were unwilling to accept some of these vales, and General Manuel Chao issued a circular[text needed] calling upon the issuers to formally request permission and to offer adequate guarantees. In consequence, on 22 September 1913 Chao issued a decree that people should accept the notes of the Compañía Ferrocarril Parral y Durango; the Alvarado Mining and Milling Company; the San Francisco del Oro Mining Company; the Concurso Mexico Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company; San Pedro, Guanaceví and E. T. (sic) Notts, Guanaceví, and not accept the Fundicion de Fierro y Bronce, the El Rayo Mining and Development Company, the Mina La Cumbre y La Bufa or any other company that was not on the list of acceptable notes{footnote}AMP, Tesorería, Tesorería, Correspondencia, caja 164, exp. 1{/footnote}.

Later on, the Minas Tecolotes y Anexas; Veta Colorada y Anexas; Mina Veta Grande y Anexas and the Cia Agricola y de Fuerzas Electrica del Rio de Conchos were added to the list{footnote}AMP, Guerra, Comandancia Militar, Correspondencia, caja 2, exp. 6{/footnote}, and on 27 September, after giving adequate guarantees, the Minas La Cumbre y La Bufa were authorised to issue notes that would be of forced circulation{footnote}AMP, Gobierno, Jefatura Política y Presidencia Municipal, Correspondencia, caja 68, exp. 2{/footnote}.

On 5 October Villa, while at Torreón, decreed that the notes issued by the various companies in Chihuahua and Durango should be accepted as legal tender until such time as they were redeemed. He, for his part, would ensure that the companies honoured their paper{footnote}¡Patria Libre!, Durango, 10 October 1913{/footnote}. In a decree of 15 December 1913 the commander in Durango, Coronel E. R. Nójera, listed the bonos of Parral amongst the revolutionary issues that were of forced circulation in that state{footnote} ¡Patria Libre!, Durango, 23 December 1913{/footnote}.

Once the Chihuahuan rebels issued their own currency, they quickly moved to stamp out other issues. On 23 December 1913 Villa ordered that the vales issued by certain Mexican and foreign-owned businesses (casas comerciales mexicanas y extranjeras) since the beginning of the revolution should be exchanged for revolutionary paper currency. However, in Parral they did not have the new currency and on 29 December General Luis Herrera, the Jefe de Armas issued a circular that the vales should continue to be accepted. Local businesses were less willing and on 31 December formed themselves into a “Unión Mercantil” that demanded that the issuers give adequate guarantees to business and the public in general{footnote}AMP, Gobierno, Jefatura Política y Presidencia Municipal, Libros minutarios, 1913, AL12-13-000-102 letter to Presidente Municipal, 10 January 1913{/footnote}.

On 6 January 1914 the Presidente Municipal received copies of the notice that only sábanas and Constitucionalist issues were of forced circulation{footnote}AMP, Gobierno, Jefatura Política y Presidencia Municipal, Libros minutarios, 1913, AL12-13-000-102{/footnote} and on 12 January the Secretario de Gobierno told him to make sure that these companies did not issue any more vales. He therefore wrote to the various companies and to the printers in the city informing them of the edict{footnote}ibid.{/footnote}.

On 23 January Governor Chao set a deadline of 31 January for exchanging these irregular issues, though on 31 January the government extended the deadline: 5 February within the city of Chihuahua and 10 February outside{footnote}Periódico Oficial, 1 February 1914. The notice refers specifically to mining scrip (vales de compañías mineras){/footnote}. Thereafter anyone in possession of such notes would be deemed a counterfeiter. Chao made a similar pronouncement in Parral{footnote}El Paso Morning Times, 2 February 1914{/footnote}.

On 12 February Silvestre Terrazas wrote to Tomás Lizárraga D., the Administrador Principal del Timbre in Parral, thanking him for the details that he had sent about these vales. It was planned to exchange them for Chihuahua money, but they did not yet have enough notes. In the meantime Terrazas instructed the Presidente Municipal to acknowledge (haga efectivos) the vales he listed with the exception of banks that did not have any branches in the state and the Concurso México Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company, who had already agreed to back their notes with their bullion{footnote}ST papers.Part I, box 84{/footnote}. The same day the Secretario de Gobierno told the Presidente Municipal to ensure that the companies redeemed immediately, in silver or on cheques drawn on a Chihuahua or foreign bank{footnote}AMP, Gobierno, Jefatura Política y Presidencia Municipal, Libros minutarios, 1913, AL12-13-000-102. Presumably paying the Tesorería rather than individual holders.{/footnote}.

Thus, the vales were gradually redeemed, although it took some time because of a delay in receiving sufficient of the new sábanas with which to replace them. It was also not without difficulties: when the Tesorero Municipal heard that the Recaudación de Rentas had received funds to make the exchange, it sent over $1,000 in vales, but the Recaudación only accepted $500, claiming that the rest were too well used, and the Administración del Timbre refused to accept other vales with which the Tesorería tried to pay its taxes{footnote}AMP, Gobierno, Jefatura Política y Presidencia Municipal, Correspondencia, caja 69, exp 1 report of Tesorero Municipal, 18 February 1914{/footnote}. On 5 March the “Unión Mercantil” was still complaining{footnote}AMP, Gobierno, Jefatura Política y Presidencia Municipal, Correspondencia, caja 69, exp 1{/footnote}.

However, it is obvious that as well as the issues during Chao’s time some companies made further issues at later dates when the shortage (or unacceptabilty) of other money demanded it. Thus, the Alvarado Mining and Milling Company and the Minas Tecolotes y Anexas were paying their workers with some sort of scrip in the first half of 1916.

On 16 December 1917 the Presidente Municipal of Parral and a special commission met with the representatives of various companies to try to resolve outstanding issues but they could discover few hard facts. Most of the companies’ representatives could claim that they were not around at the relevant time and unfortunately (or conveniently) most records had been destroyed{footnote}AMP, Gobierno, Jefatura Política y Presidencia Municipal, Actas, caja 23, exp 19{/footnote}.

The companies or individuals who issued vales were:

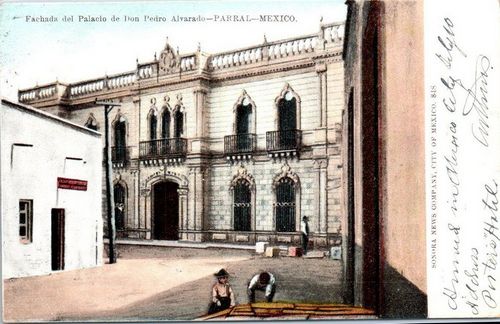

The large Alvarado Mining and Milling Company operated the mine at La Palmilla, just outside Parral. In 1907 the wealthiest man in Mexico was Pedro Alvarado, a poor labourer who made an immense fortune within a few years from this mine. As a patronising and racist American newspaper article reported: “Once a poor miner, almost on the verge of beggary, he was, through many tribulations, animated by a faith in providence and in his mine in the side of an unknown hill near Parral. How he dug there, hiring labor when he could, and working alone when he could not, and how at last, within the life span of the youngest child who could read these lines, he struck the great bonanza which has made him one of the wealthiest men In the southern republic, make a story of thrilling interest. Alvarado is ignorant and narrow, a man in whose hands wealth is but a toy. Yet he has accepted that toy with a religious conviction that It is in the nature of a trust. As coming from Mexico’s soil, he has said that it belongs to Mexico, and a stancher patriot or a patriot who showed more by his works, never lived. It Is said that he has offered to pay the national debt of his country. He is a home-trader, however, and buys his goods of local merchants, giving preference to home products. He Is a generous philanthropist, and distributes alms among the poor with a lavish hand. Pedro Alvarado lives in a palace of many rooms, fitted in magnificent taste. Yet that palace is oppressive to him - just why, he does not understand - and his favorite room is the wine cellar half under ground. Not that he is too fond of its contents, but because he finds In the rough simplicity of the cellar the relief which he craves. There, a few weeks ago, the writer talked with him, as the millionaire sat on a case of imported champagne, drinking Mexican beer. He Is a man of small stature, judged by American standards, yet having considerable native dignity and poise. He is but 36 years old, and looks no more. A slight black mustache and beard, and ill-fitting black broadcloth suit, a made-up black satin cravat, in which glistens an immense diamond pin, which shines no more than his little black eyes, describe the man. Alvarado’s wealth is estimated by generous correspondents at $150,000,000. He is probably worth one third as much, and holds sole title to a mine which is now producing about $1,500,000 net profit each year, but which, under progressive management, no doubt could give double, or even three times, that amount"{footnote}Sacramento Daily Union, Vol. 112, No. 165, 5 February 1907{/footnote}. It is not surprising that Alvarado was sympathetic to Francisco Villa.

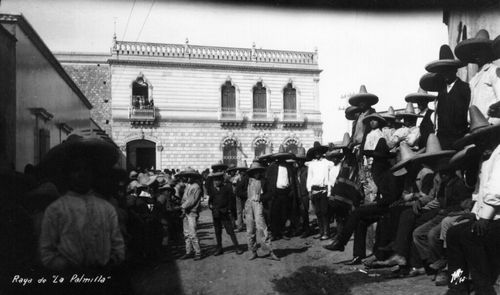

Payday at La Palmilla. The large house in the background is the Palacio Alvarado

| date on note | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 50c | ||||||

| $1 | [ ] April 1913 | |||||

| [ ] May 1913 | ||||||

| 10 July 1913 | includes number 8910 | |||||

| [ ] August 1914 | ||||||

| [ ] September 1914 | ||||||

| [ ] October 1914 | ||||||

| [ ] November 1914 | ||||||

| $10 | 19 May 1913 | see comment below |

The Alvarado Mining and Milling Company must have issued at least three different denominations in 1913, viz. 50c[image needed], $1, and $10[image needed] though only the $1 note is known. When Lorenzo Frauco was arrested in Parral in December 1913 for counterfeiting he had in his possession $177.50 in notes of the company, hence the 50c; the $1 is known dated 10 July 1913; and a forged $10 note, numbered 15246 and dated 19 May 1913, was an exhibit in another trial{footnote}Unless the $10 note was an altered $1 note. AMP, [ ]{/footnote}.

The notes were printed by The Printman, a printing press in Parral owned by A. L. Cohoon (sic), that also produced the Parral Miner.

They were guaranteed by J. McQuatters, a major shareholder, with the security being lodged in an El Paso bank, and signed by a Long as cajero. At the time the general manager was a James I. Long and the accountants (contadores) Johnson and Long{footnote}AMP, Gobierno, Jefatura Política y Presidencia Municipal, Actas, caja 23, exp 19{/footnote}.

These notes were redeemed in sábanas.

In June 1916 the Presidente Municipal Interino of Parral, José de la Luz Herrera, reported to Chihuahua that the Alvarado, without oficial authorisation, was again paying with vales[image needed], that had a guaranteed value of 25c oro americano, and that this was having a depreciating effect on the recently introduced infalsificables{footnote}AMP, Gobieno, Jefatura Política y Presidencia Municipal, Libros Minutarios, AL12-13-000-103{/footnote}. On 22 July 1916, probably on the prompting of the Chihuahua government, de la Luz Herrera wrote to Carranza urgently asking whether the company could continue paying in these vales{footnote}AMP, Gobieno, Jefatura Política y Presidencia Municipal, Libros Minutarios, AL12-13-000-111{/footnote}. Given that Carranza was a stickler for constitutionalilty, he will almost certainly have refused, but the company soon after suspended operations when General Jacinto B. Treviño prohibited the export of silver.

The company’s local records were destroyed when Villa seized them in November 1916.

On 13 March 1918 the Oficial Mayor in Chihuahua, J. A, Enríquez, issued a notice to the holders of the vales al portador issued by the Alvarado Mining and Milling Company in 1913 and 1914{footnote}Periódico Oficial, 23 March 1918{/footnote} that they had six months in which to redeem them. The notice set the various rates of exchange for the different issues, based on the official index of inflation{footnote}at par oro nacional for the notes issued in April and May 1913; 62c for July 1914; 53c August 1914; 40c September and October 1914, and 39c for November 1914{/footnote}. No mention is made of any 1916 vales, so they cannot have been a substantial issue.

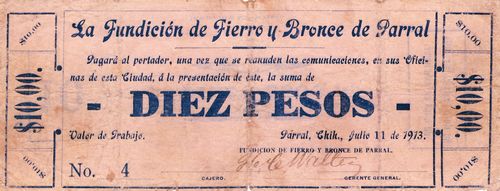

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| $1 | 1 | 999 | 999 | $999 | includes numbers 91 to 986{footnote}CNBanxico #10108{/footnote} |

| $5 | 1 | includes numbers 61 to 565 | |||

| $10 | 1 | includes numbers 4 to 100 | |||

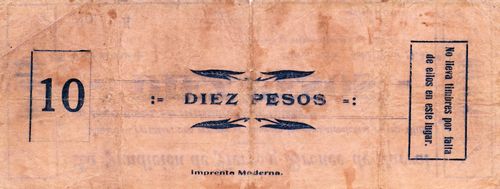

La Fundicion de Fierro y Bronce de Parral issued valores, for one, five and ten pesos, dated 11 July 1913 and signed by H. C. Walters.

|

An H. C. Walters (sic) was reported running the Parral foundry in January 1912{footnote}El Paso Herald, 27 January 1912{/footnote} and an H. C. Walter (sic) was issued with the title to El Cometa Hailey mine in Minas Nuevas, Hidalgo del Parral in September of that year{footnote}Boletín Oficial de la Cámara Minera de México, 1 October 1912{/footnote}. On 2 January 1914 H. C. Walters (sic) “who said he owned several thousand acres in Chihuahua, including mining concessions” arrived in New Orleans on the steamer City of Mexico as a refugee from Veracruz. He said he was forced to pay the rebels $2,000 to get out of jail at Santa Rosalia (now Camargo). Americans in his section were disheartened, he said, because Carranza followers looted their ranches{footnote}Albuquerque Morning Journal, 3 January 1914{/footnote}. |

|

Examples of these notes were unknown until 1984 when a large group consisting of $1, $5 and a single $10 came onto the market, but we already knew of their existence because in a letter of 27 October 1913 to the Jefe de Armas in Parral Francisco Villa wrote

DIVISION OF THE NORTH

PERSONAL CORRESPONDENCE

COMMANDER IN CHIEF

Camargo, Chihuahua

October 27, 1913

Mister Chief of Arms,

Parral, Chih.,

Dear Friend:

Mrs. Manuela Ayala de Chacon, who lives in the city, has in her possession the sum of $1,000.00 (one thousand pesos) in paper money issued by the Iron and Bronze Company of Parral, Chihuahua, and signed by the General Manager of the same, Mister H. C. Walton, although the supreme reason of the interruption of communication lines has forced the company to issue the aforesaid documents and has further caused major problems to the poor people by leaving in their possession documents of this nature without any current value and therefore difficult to exchange into money.

In view of the foregoing, please declare that the aforesaid sum of one thousand pesos should be extended in a money order on a foreign exchange, the idea being that it must be in American currency without any discount, so that through the local mayor the bonds of the aforesaid Senora Chacon should be picked up and handed over to the Iron and Bronze Company.

Sincerely yours,

Francisco Villa{footnote}letter by permission of Ing. Benjamine Herrera Vargas in Mexican Revolution Reporter, 15, November 1979{/footnote}.

The Parral and Durango Rail Road Company made an issue[image needed] in 1913 to pay its workers because of the shortage of banknotes{footnote}{/footnote}, though its representative thought that the total amount was very insignificant, and might have made another issue in 1916. The notes were signed either by Robert J. Long, the general manager, or by J. Reno Wilson. Unfortunately, the company’s records were reduced to ashes in one of the Villista raids{footnote}AMP, Gobierno, Jefatura Política y Presidencia Municipal, Actas, caja 23, exp 19 evidence of Manual Cortés{/footnote}.

| Robert J. Long was the brother of James I. Long and assistant manager of the Hidalgo Mining Company. He was appointed assistant manager of the Parral and Durango Rail Road Company in August 1906{footnote}The Mexican Herald, 13 August 1906{/footnote} and succeeded his brother as general manager on 14 November 1909{footnote}The Mexican Herald, 15 November 1909{/footnote}. | |

| J. Reno Wilson |

Santa Bárbara is a historic mining town about twenty-five kilometres south-west of Parral.

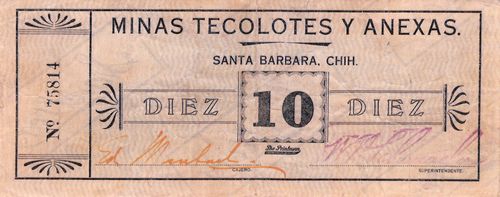

The Minas Tecolotes y Anexas in Santa Bárbara were part of the American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO). In March 1913 General Manuel Chao had approached the managers there, demanding $5,000 to pay for the “protection” provided by his troops. When the superintendent, W. P. Schumacher, refused the demand, Chao explained that without the money, he might not be able to prevent his own forces from raiding the mines. Schumacher reluctantly gave General Chao $2,750{footnote}Washington National Records Center, Record Group 76, Mexican Claims Division, Awarded Claims, 1924-1938, box 221, docket 2312{/footnote}.

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| $10 | includes number 75814 |

The company issued a $10 note in 1913, also printed like other companies' valores by the Printsman press, with the inkstamped signature of the cashier (cajero) and superintendent (superintendente). These were issued later than the Parral notes because coinage continued to circulate longer in Santa Barbara and the company was able to pay in efectivo when in Parral they had already issued notes{footnote}AMP, Gobierno, Jefatura Política y Presidencia Municipal, Actas, caja 23, exp 19{/footnote}. When the coinage dried up the local authorities and commerce suggested the vales, which represented money drawn on Mexico City or El Paso{footnote}AMP, Gobierno, Jefatura Política y Presidencia Municipal, Correspondencia, caja 69, exp 1 letter of superintendent Gilbert, 21 February 1914{/footnote}: these were redeemed in legal tender{footnote}AMP, Gobierno, Jefatura Política y Presidencia Municipal, Actas, caja 23, exp 19{/footnote}.

| Ed Mau[ ][identification needed] |

|

| W. P. Schumacher |  |

These $10 notes were counterfeited, as a Teódulo Talamantes had presented a false note in the company’s offices, and then asked the local authority to start an investigation{footnote}ibid.{/footnote}.

On 21 February 1914 the company’s superintendent, L G. Gilbert, reported to the Presidente Municipal in Parral that the company had not been using their notes (contraseñas) for some time though it was difficult to redeem them because of the lack of sábanas and asked for permission to make payment in banknotes (billetes de Banco) for sums greater than five pesos, and in their own $1 notes for smaller amounts{footnote}ibid.{/footnote}.

When the company renewed operations in 1915/1916, because the public was refusing to accept the legally-forced Carrancista currency, the company’s employees themselves asked to be paid with vales of 25 centavos oro (americano)[image needed]. These were later redeemed and by December 1917 only $126.75 was outstanding{footnote}ibid.{/footnote}.

The Tecolotes mines are still being worked by Grupo México.

The Veta Colorada mine was also in Santa Bárbara.

The El Rayo Mining and Development Company was an American-owned mine in Santa Bárbara.

| series | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

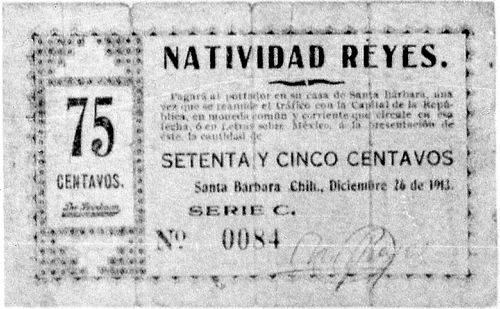

| 75c | C | includes number 0084 |

Natividad Reyes, of Santa Bárbara, issued a 75 centavos valor, Series C, dated 26 December 1913 to be paid in his casa (commercial) once traffic with Mexico City had been renewed.

| Natividad Reyes |  |

These notes were not included in Chao's decrees.

The Veta Grande y Anexas, at Minas Nuevas (now Villa Escobedo) was also part of the ASARCO group of companies (like Minas Tecolotes y Anexas) but issued its own vales.

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 25c | includes number 0227 | ||||

| $5,000.00 |

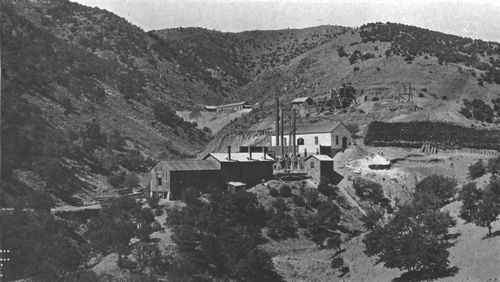

The Minas de la Cumbre y la Bufa were at Roncesvalles, ten kilometres south of Parral.

In 1913 Georges Chabriere, the mines’ engineer (ingeniero) issued $5,000 in vales. A valor for twenty-five centavos is known.

| Georges Chabriere |  |

By 27 September 1913 Eduardo Ricaud, representing the Casa Comercial “A. Ricaud y Cia.” had provided an adequate surety to the Cuartel General in Parral and the notes were declared of forced circulation{footnote}AMP, Gobierno, Jefatura Política y Presidencia Municipal, Correspondencia, caja 68, exp. 2{/footnote}. A Ricaud y Cia ran the "Fabricas de Francia", situated in the Plaza Hidalgo, but on 28 February 1914 was forced to close down because of a shortage of stock.{footnote}AMP, Tesorería, Tesorería, Correspondencia, caja 165, exp. 1{/footnote}. In November Alejandro Ricaud was kidnapped and murdered, even though his wife paid his ransom.

San Francisco del Oro is a beautiful mining town, about fifteen kilometres north of Santa Bárbara. The mine is still being worked and the ore is carried across the town to the crusher on an aerial tramway.

The San Francisco del Oro Mining Company Limited was an English company, with most of its properties within San Francisco del Oro.

This company issued notes[images needed] in 1913 and redeemed them early in 1914.

On 11 February 1914 the manager of the El Caballo, Miguel Tinoco, was robbed in Jiménez and among other things the thief, José Barcenas, took a packet of cancelled notes. Barcenas was a linesman (celador de telegrafos) on the railways, working between Ortiz, Ciudad Chihuahua and Ciudad Juárez. He lent $80 (in sixteeen $5 notes) to Bernardino Galindo, who spent two in Parral. When these were shown to Tinoco to check if they were valid or not, Tinoco was able to identify the miscreants and Galindo was subsequently arrested in Santa Bárbara with the other $70. Senora Dolores Herrara, of Santa Bárbara, had also received a cancelled $5 from Felipe Camarillo, who was in charge of repairs to the railway (cabo de reparaciones de la via de los Ferrocarriles Nacionales). An order for Barcenas’s arrest was sent to Chihuahua on 18 February{footnote}AMP, Gobierno, Jefatura Política y Presidencia Municipal, Libros minutarios, 1913, AL12-13-000-102{/footnote} and passed on to the Inspector General de Policía on 22 February{footnote}Almada Collection, roll 810, 1472{/footnote}.

However, the company could also have issued notes in 1916 because in 1917 its representative, Isaac Zepeda, reported that notes were redeemed mostly in gold, silver or in dollars at a rate of two for one, and very few notes were outstanding (unless he was referring to the late redemption of 1913 notes, or did not want, in 1917, to acknowledge that the company had redeemed them with Villista currency){footnote}AMP, Gobierno, Jefatura Política y Presidencia Municipal, Actas, caja 23, exp 19{/footnote}.

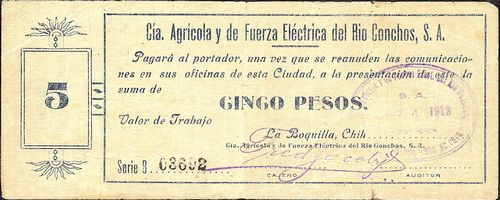

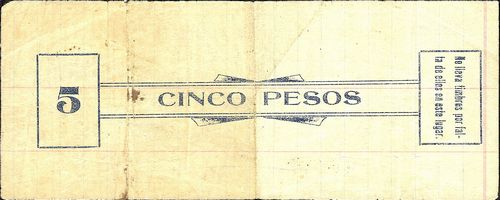

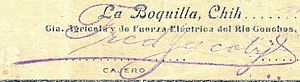

A similar issue, also to be redeemed once communications were re-established, was made by the Compañía Agricola de Luz y Fuerza del Río Conchos, which was based in La Boquilla, 90 kilometres north-west of Parral.

| series | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| $5 | D | includes number 03692 |

The Compañía Agricola de Luz y Fuerza del Río Conchos, S.A. gained its concession, including the establishment of a tienda de raya, on 7 December 1906. On 23 October 1909 it was granted a concession to build a railway from Ciudad Camargo to La Boquilla. It built the dam at La Boquilla from 1910 to 1916, during the height of the revolution.

We know of a valor de trabajo for five pesos, dated 4 August 1913.

| Fred Jacoby |  |

Although geographically in Durango, Guanaceví had close ties with Parral and various issues from there circulated and were the subject of pronouncement in Parral. These are dealt with in the Durango and consists of the Concurso México Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company, E. F. Knotts, and the Jefatura Municipal.

In 1913 with the resumption of hostilities, the interruption to traffic and the increase in value of silver coins, many areas experienced a shortage of small change and various concerns issued fractional paper currency. Besides the vales issued around Parral we know of the following:

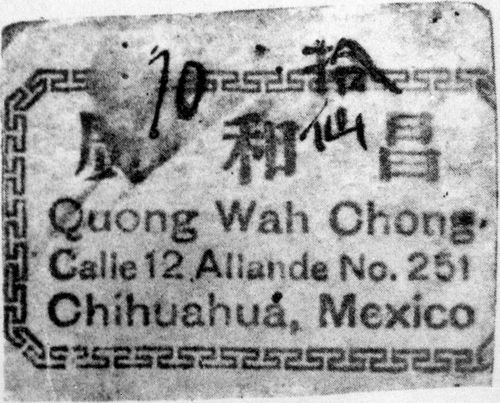

We have an example of a note issued by Quong Wah Chong of Calle 12, Allende No. 251, Chihuahua

Another possible issuer was the American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO). ASARCO was owned by the Guggenheims and began its activities in the state in 1880 with the purchase of the Tecolotes mine. In 1905 it received a twenty year concession to establish a planta beneficiadora de metales and set up an ‘Anglo-American island’ at Avalos, just outside Chihuahua, on land donated by Luis Terrazas. The tienda de raya was run by Juan Terrazas, Luis’ son.

Once the revolution broke out this company found it necessary, in order to continue operating in certain areas, to provide food and clothing for its workers and even to issue its own scrip when the faction in control failed to provide a currency or when the money it printed lost its value{footnote}Isaac F. Marcossan, Metal Magic : The Story of the American Smelting and Refining Company, New York, 1949{/footnote}. ASARCO produced a $1 note in Aguascalientes in January 1914 and might have produced notes for its plant at Avalos{footnote}In June 1913 the smelter had been closed for some time but was hoping to re-open (Mexican Herald, 29 June 1913). The Mexican Herald reported, on 9 February 1914, that ASARCO had been obliged to issue vales where it had smelters in operation but in June 1914 Avalos was paying its employees in pesos fuertes del cuño mexicano (Almada, 4298){/footnote}.

The Compañía Ferrocarril Mexicano del Norte was established on 26 June 1890 in New York by Robert S. Towne, George Foster Peabody and Associates, based on a concession granted on 20 March 1890. The line was built by the Ferrocarril Central to connect the station of Escalón, Chihuahua, with that of Sierra Mojada, Coahuila, with a 133-kilometre line that was opened in 1891. The line was seriously affected during the Revolution.

Among the archives that were thrown into landfill by the new owners of the American Bank Note Company was correspondence from 1908-1916 on notes for the Compañía Ferrocarril Mexicano del Norte{footnote}ABNC, 40241.00{/footnote}. This might have been for a proposed (and possibly effected) issue of notes, to be used to pay workers and suppliers, during the Revolution.

Once the Chihuahuan rebels issued their own currency, they quickly moved to stamp out other issues. On 23 December 1913 Villa ordered that the vales issued by certain Mexican and foreign-owned businesses (casas comerciales mexicanas y extranjeras) since the beginning of the revolution should be exchanged for revolutionary paper currency. On 31 January 1914 the government set a new deadline of 5 February for exchange within the city of Chihuahua and 10 February outside{footnote}Periódico Oficial, 1 February 1914. The notice refers specifically to mining scrip (vales de compañías mineras){/footnote}. Thereafter anyone in possession of such notes would be deemed a counterfeiter.